Books

Books

Look inside ⇩

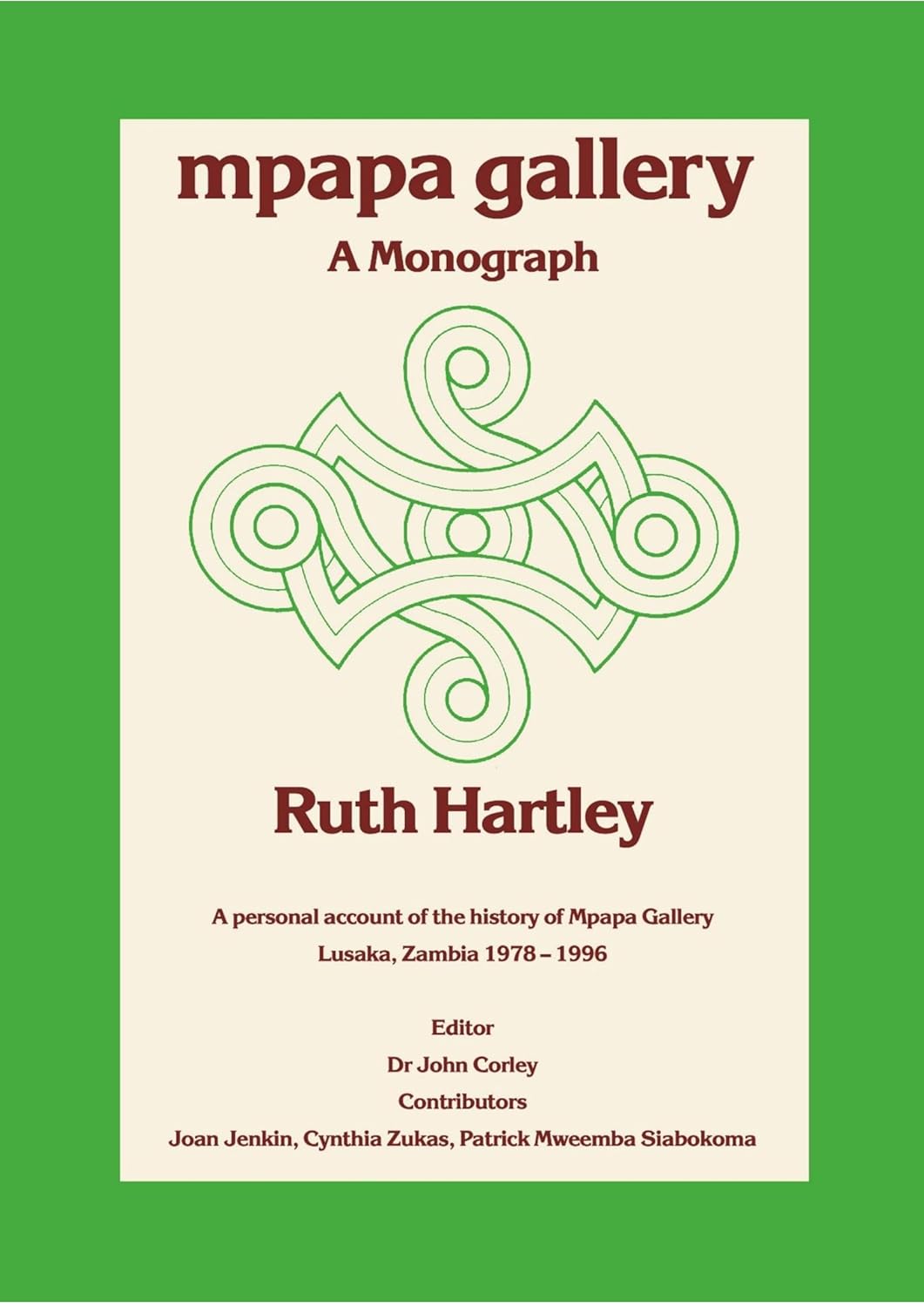

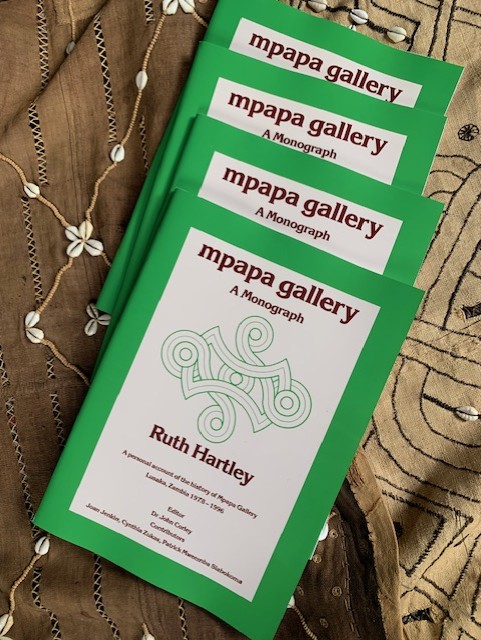

Mpapa Gallary

BY RUTH HARTLEY

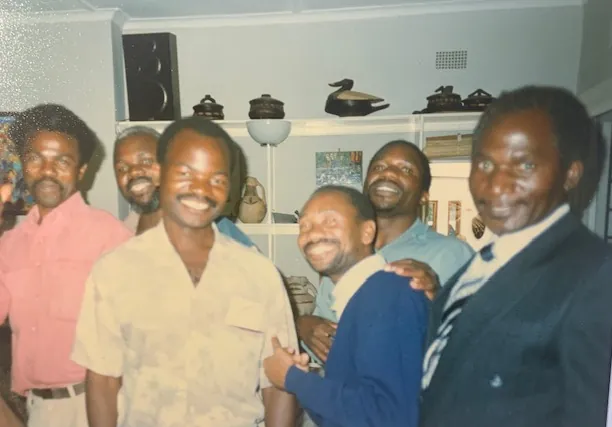

The Mpapa Gallery was begun by Joan Pilcher, Heather Montgomerie, Cynthia Zukas, Patrick Mweemba and me, all people who were passionate about art and positive about the newly independent country of Zambia.

So too, were all the people who connected with the gallery as artists, art enthusiasts, art collectors, art advisors, funders and supporters, workers, managers, visitors and friends.

Art galleries almost never make any money, so they are usually run as charities with endowments. Above all, it is the creative people and artists who make it possible. All forms of the creative arts are the lifeblood of every nation.

Mpapa Gallary

By Ruth Hartley

The Mpapa Gallery was begun by Joan Pilcher, Heather Montgomerie, Cynthia Zukas, Patrick Mweemba and me, all people who were passionate about art and positive about the newly independent country of Zambia. So too, were all the people who connected with the gallery as artists, art enthusiasts, art collectors, art advisors, funders and supporters, workers, managers, visitors and friends.

Look inside ⇩

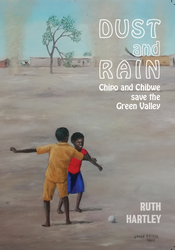

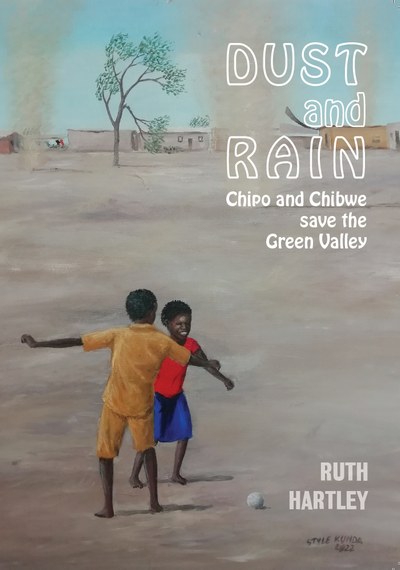

Dust and Rain

BY RUTH HARTLEY

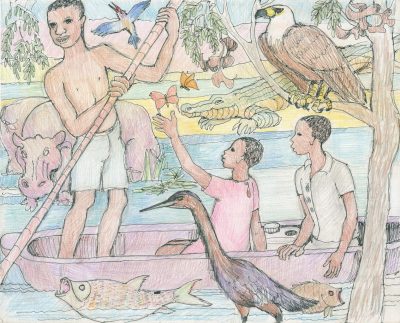

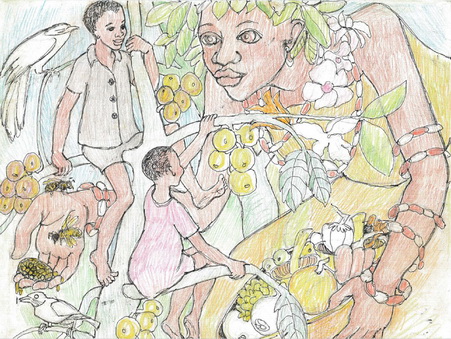

Chipo and Chibwe save the Green Valley

Two children make a perilous journey through the heart of modern and magical Africa to save their parents’ farm in the Green Valley from drought and climate change.

Kambili and the drought arrive in a whirlwind of dust into the lives of CHIPO, an eleven-year-old girl with a special gift, and her brother, CHIBWE.

Without rain, the family can’t grow food. so the children run away to find Makemba, the Wise Woman in the Evergreen Forest who can teach them how to keep their valley green.

They are kidnapped by criminals but escape and have extraordinary adventures as they journey to find Makemba and then take her magical river water to save the Valley and end the drought.

Dust and Rain

By Ruth Hartley

"... facts are woven in a colourful tapestry of magic and adventure with talking animals, birds and insects, and mythical creatures who tell us in crystal clear language of their role in the environment. ... I recommend this book as a school reader and textbook. ... A stupendous odyssey."Verona Mwelwa, Teacher

"This inspiring children’s book about conservation and good agriculture practice … should really be considered for the school curriculum."Guida Belcross, Lusaka Recycling

Look inside ⇩

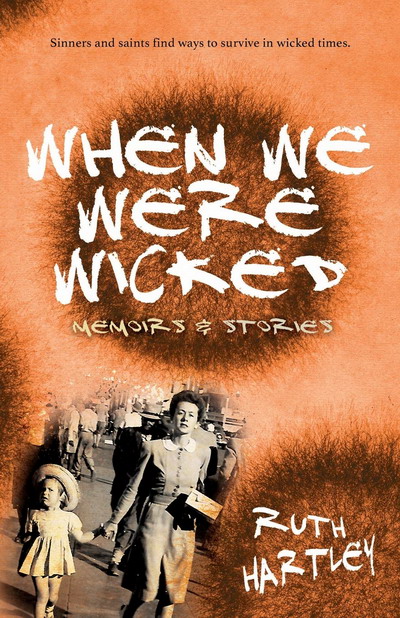

When We Were Wicked

BY RUTH HARTLEY

In a wicked world are there any innocent survivors?

Sinners and saints, villains and heroes, the children, women and men in these stories all find ways to survive in wicked times.

Some of these stories are old and were written down decades ago. Some are new.

Some of these stories make me laugh. Some stories were inspired by my ill-spent youth. Some are wicked inventions.

Two are short memoirs about wicked people. I fell over them so often in dark dreams that I was forced to dig them out of the sludge of my memory and expose them to light.

"I was so much older then, when I was young." — as Eric Burdon and the Animals sang in 1967

When We Were Wicked

By Ruth Hartley

"... the lean style gave it authenticity, helped by your acute and sensitive selection of detail — such as your mother 'winding the windows until they were almost shut.' The sparseness of your prose (is) the product of years of shaping and moulding words and phrases, mastering that art called 'writing'."Michael Holman, FT Africa Editor, 1984–2002

Look inside ⇩

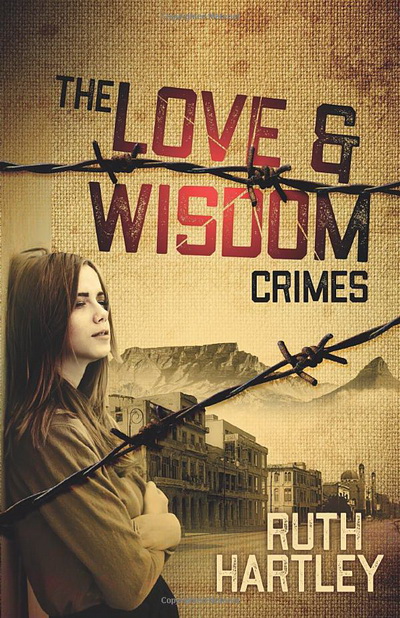

The Love and Wisdom Crimes

BY RUTH HARTLEY

A coming of age adventure story about a young woman who discovers that, in apartheid South Africa, it is dangerous to love a revolutionary and a crime to love someone black.

Trying to make sense of her past and her present, Jane visits the South Africa of her youth and finds that the conflicts of her life then have their echo in her life now.

An accompanying book of poetry, The Spiral-Bound Notebooks, contains the poems that inspired this novel.

Ruth Hartley said, "I want my readers to live inside my stories and experience them as ‘true’ even though they are fictional, even when I rework my own life experiences.

It seems absurd to me, though probably not to my children, that my novels set in my youth slot into the genre of historical fiction. When I write a novel, I’m creating a world in which all the characters are true to themselves."

The Love and Wisdom Crimes

By Ruth Hartley

Deft, impressive writing, evocative of place and time in which political dangers lie hidden like land mines.

Jane's story of travel from a peaceable, silent life at the home farm to the city where she is catapulted into an underground anti-apartheid political intrigue, ... skilfully draws the reader in as we hold our breath for her and her friends. ... a lyricism ... points up the contrasts of Africa, (its) sheer beauty and the terrible ugliness of the politics.Claudia Nayler

Look inside ⇩

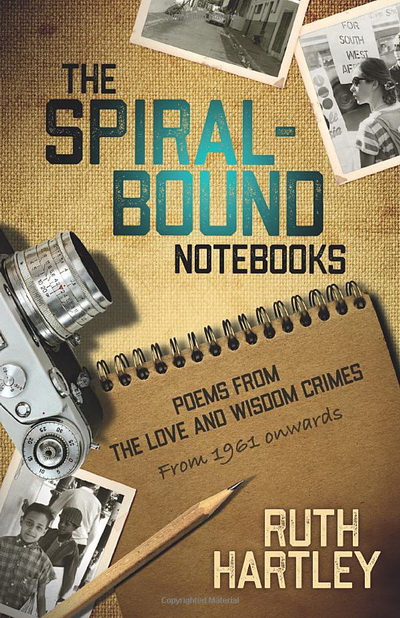

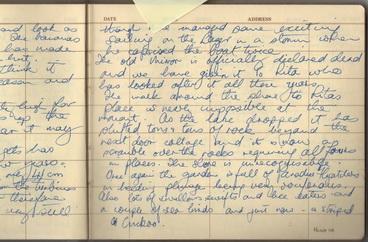

The Spiral-Bound Notebooks

BY RUTH HARTLEY

"My notebooks contain not just the marks of a pen, but the living memories that glued me and my soul together as I journeyed through life. I really don’t know how they survived for so long. Sometimes all that a refugee or a migrant can carry from home are the words and music of a song.

Most of the poems in this chapbook come from my life in South Africa but some were written in secret during my married life in Zambia. I hid them away in a blue folder in the spare room that doubled as my sewing room and writing study.

Perhaps it is in these private creative spaces that our human freedoms are made and preserved?"

The Spiral-Bound Notebooks

By Ruth Hartley

"Many of the poems ... recall this time of unrest and confusion in South Africa. Ruth captures the feel of the country, the poverty, the damage, the loss of freedom, she mixes her fear and anger at the time with images of the Africa she had grown to love. There were times when she feared for her life due to her close connection with the anti-Apartheid movement."Kate Rose, Bonjour Limousin

"I began to write poetry in spiral-bound stenography notebooks while at university in South Africa. It was a way of resisting apartheid but also of discovering who I was and wanted to become. Poetry can be an intense and economic diary. The notebooks came too when I ran away to London and by some miracle are still with me today. They remained hidden for long years until their ideas germinated into more poetry, my novel, The Love and Wisdom Crimes and my memoir, When I Was Bad" Ruth Hartley

Look inside ⇩

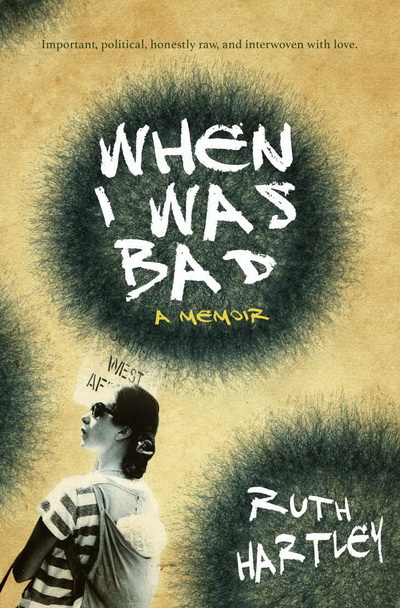

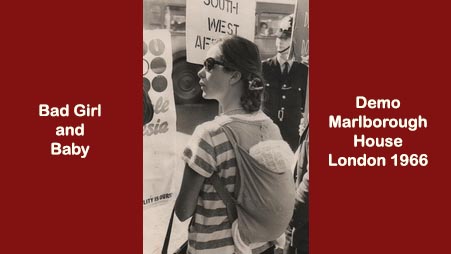

When I Was Bad

BY RUTH HARTLEY

In the 1930s George Bernard Shaw's black girl searches for God, but settles down in a garden with an Irish socialist. In 1966 I was the bad white girl — an unmarried mother and a criminal according to the laws of South Africa.

My 1996-1997 memoir of love and exile starts on Victoria Station. Exile is not a word on paper but a lived experience. It is a lonely, bitter place of loss and nostalgia, as I had yet to find out. It’s the opposite of home. I was exiling myself to a place I didn’t know, where I had no friends or relatives. Exile is not a holiday trip. You can’t travel back from it. Exile is loss; it’s a version of dying.

I wasn’t sure whether my family would cast me out when they learnt the real reason I was in England. At that moment on Victoria Station it was too late for a change of plan. But I’d never thought that going home was a real option anyway.

When I Was Bad

By Ruth Hartley

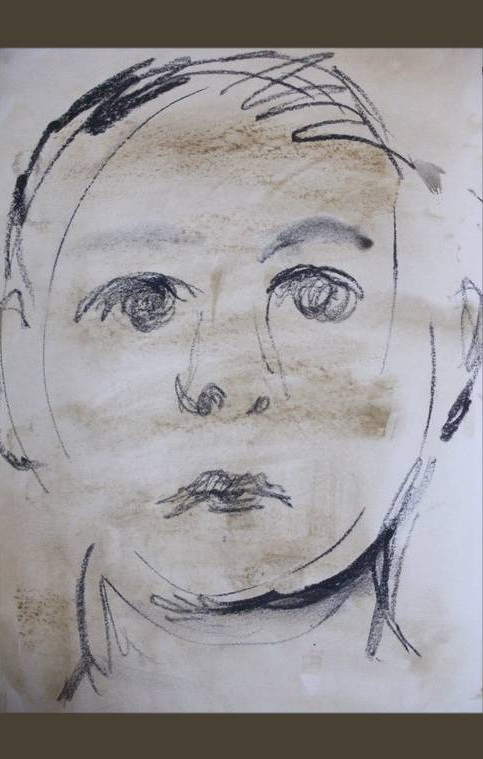

“A memoir is not a story where the characters are understood from inside to outside by their creator. It is a steamy mirror on which I draw a self-portrait with a damp finger. It is supposedly a reflection of what I was, but it can’t be that exactly because it is made by me as I am now. No amount of soul-searching can take me far enough out of myself to objectively describe my actuality.

Ruth Hartley

Look inside ⇩

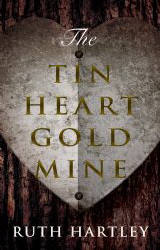

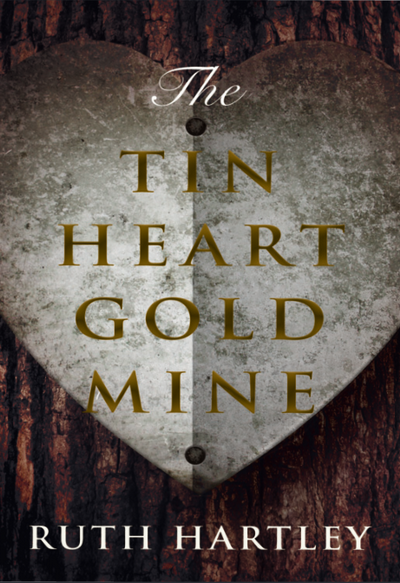

The Tin Heart Gold Mine

BY RUTH HARTLEY

Heart of Darkness and Lust for Life collide as the Cold War in Africa gets hot.

Lara, the artist, loves Oscar, a suave, older entrepreneur, and owner of the Tin Heart Gold Mine. She also loves Tim, a journalist seeking truth.

The Tin Heart Gold Mine is a dramatic story, about vibrant, intriguing characters passionate about art, love, the making of money and the African bush, whose lives become entangled in war and politics.

How well do we ever know the people we love?

The Tin Heart Gold Mine

By Ruth Hartley

On her way, artist Lara encounters Tim, an idealistic foreign correspondent, and Oscar, an older man with a mysterious past. At the end you are left with doubt — Will Tim come back? Can Oscar really be dead? and who is the father of Lara’s child? A fascinating read!

John Corley

Ruth Hartley on Talk Radio Europe, Spain, March 2017

Look inside ⇩

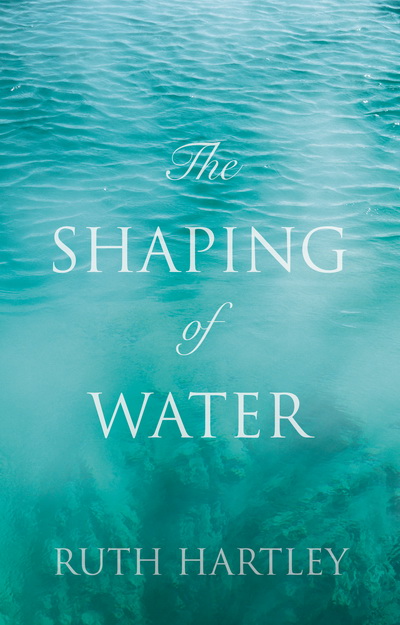

The Shaping of Water

BY RUTH HARTLEY

The vast man-made Lake Kariba in Zambia is built on political and geological fault lines. Built to generate power and maintain colonial power, it drowns a valley and displaces Milimo and his mother Natombi.

Charles and Margaret love the lake and their holiday cottage on its shore, but their way of life is endangered. Marielise and Jo take respite at the cottage from their exhausting battle against apartheid. Manda and Nick confront their damaged relationship.

They are all connected by a secret known only to the priest, Father Patrick.

The Shaping of Water

By Ruth Hartley

A very good read. Interconnected lives are affected by the creation of the Kariba dam. The unintended consequence is an altered ecosystem and the separation of populations and countries. ... Visitors leave comments in the guest book of a cottage on the lake shore. The water level rises and falls and the natural world of plants and birds is woven into the story in brilliant passages of calm in the midst of turmoil.Polly Loxton (Amazon UK 28/01/14)

The Cottage Guest Book

Look inside ⇩

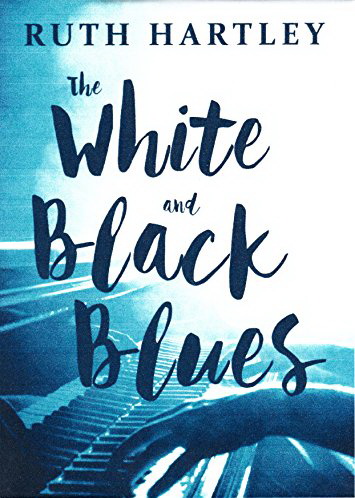

The White and Black Blues

BY RUTH HARTLEY

I released this short story collection to coincide with Marciac Jazz Festival 2016, as a free paperback to promote my novels.

The title story, The White and Black Blues, tells how Tom Waller was born in the wrong skin in Africa.

His friendship with black jazz musicians transforms his life, and takes him on a long journey away from his harsh father and their failing farm in Africa, but he must still discover who he really is “under his skin”.

This story grew out of my memory of the visit of the great Louis Armstrong to Rhodesia in 1960 and the pleasure I have in jazz today.

The White and Black Blues

By Ruth Hartley

"Skokiaan" is a tune by Rhodesian (Zimbabwean) musician August Musarurwa (aka Msarurgwa, d. 1968) in the tsaba-tsaba big-band style that succeeded marabi. Skokiaan (Chikokiyana in Shona) refers to an illegal self-made alcoholic beverage. Within a year of its 1954 release in South Africa, it reached No. 2 on the USA Cash Box charts. Many artists produced interpretations, including Louis Armstrong, who performed it in Rhodesia as recorded in the title story .

Ruth Hartley

Look inside ⇩

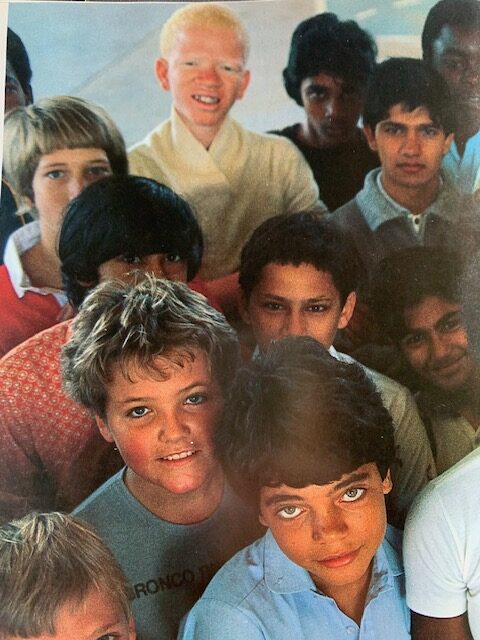

The Colourless Child

BY RUTH HARTLEY

2 - Packing

Cheelo's Skin

Nobody can stay alive if they have no skin. My skin protects me from rain. My skin protects me from infections. My skin is sensitive to the changes in weather.

Soon after the secret meeting at the restaurant, Mom and Carl tell me they’ll be travelling all over the Republic during their campaign and as I’m only nine - almost ten, I can’t stay home alone. I’ll be safer with Natasha’s Auntie Hannah in the Old Kingdom until the election is over. Mom will take me and Natasha on the aeroplane to Hannah’s house and Natasha will stay there to study art. Right now, my stepsister is doing that thing my mother does – she arches her back and turns her head sideways as if she can see me better when she’s all twisted up and that little bit further away. I wriggle, hump one shoulder towards her and keep my head down as if I’m admiring my new trainers. Then I do my cute look up at her from under my white eyelashes, with my bottom lip pushed out. Natasha laughs, but she isn’t happy.

The Colourless Child

By Ruth Hartley

An NBC News article asks, "Do white artists have the right to depict Black pain?" Art professor Dr. Lisa Whittington says, “As artists—responsible artists—we are to speak and to document history. We are to tell about life from our point of view from where we stand.”

Must white artists limit themselves to their own culture or their guilt and wrongdoing vis-à-vis other cultures? Who says so? History? Culture? Society? Can I explore injustice and oppression only if I have identical experiences? How do Germans face up to the Holocaust or South Africans to apartheid? My characters face these questions.

Ruth Hartley

MORE INFO

Join Ruth's mailing list

Dust and Rain

BY RUTH HARTLEY

Excerpt

CHAPTER ONE - THE WHIRLWIND

Something bad is going to happen.

My name is Chipo. Ma says I’ve a gift that allows me to feel things that other people can’t. Maybe that’s true. When I look up, I can see that the sky isn’t blue. It’s white-hot and so thick with dust that it’s difficult to breathe. I know that something up there is watching us. Something is swirling up above us in circles that come closer and closer. I know it’s not just the heat pressing on my head that makes me feel dizzy.

We all went out to help plough the fields this morning but the ground is so hard that Pa and Ma had to give up. They’ve gone back to the farmhouse leaving my brother, Chibwe, and me on our own with nothing to do. Chibwe is over twelve years old and I’m nearly eleven. Pa says Chibwe lives up to his name, which means a little rock, but Ma says Chibwe could learn from me.

‘It’s all very well being determined, Chibwe,’ Ma says. ‘It’s a good idea to think first and use your common sense, like Chipo.’

We made faces at each other when Ma said that but we don’t often fight. More often we end up by doing something together like playing one-person-a-side football, even though I’m a girl.

‘Come on Chibwe!’ I say after Ma and Pa have left. ‘I’m thirsty – let’s find somewhere shady to sit by the river.’

‘It’s too far to walk and I’m hungry,’ Chibwe says. ‘Let’s look for bush fruit under the palm trees instead.’

That’s one of our favourite places to play, so I agree. I like to collect the round fruit that falls from the palm trees. If the skin is soft and green it's good to chew and the hard ivory seeds are so beautiful I like to collect them.

‘What happens if there is no rain and Pa Mulenga and Ma Chiluba can’t grow any maize or vegetables this year?’ I ask Chibwe. I know what will happen, of course. I’ve seen the worried looks on Pa Mulenga and Ma Chiluba’s faces.

‘We’ll die of hunger — we’ll starve,’ Chibwe says. Then he looks at me sideways and adds, ‘It’s a joke Chipo! We’ll just eat less.’

We start to run towards the palm trees and, as we do that, I feel as if the earth is lifting under my feet. Dead leaves and grass swish around our ankles and the air fills with blown sand.

‘Watch out!’ Ma Chiluba calls out from the path back to our house. ‘There’s a whirlwind coming our way!’

It is a really huge whirlwind. A towering tornado of dust, one of those strong spinning winds that happens in the heat before the rainy season. They whip around tearing branches from trees and sometimes take the roofs off houses.

‘Witches ride in these twisting dust storms,’ Grandmother Mutende once told us. ‘Point your smallest finger at the whirlwind so the witch doesn’t come close to you.’

The Tin Heart Gold Mine

BY RUTH HARTLEY

Excerpt

Chapter Four - The Poachers

Lara returned to Bill and Maria's camp filled with enthusiasm and self-confidence. Jason had arrived a week before her and was busy setting up the summer camp inside the National Park.

“Things don't look good this year.” It was unusual for Bill to look tired at the start of the season but the day was unseasonably hot and the dusty wind irritating. “The rains were very poor. River levels are much too low. The best water holes are drying up. Bush cover is sparse. We are going to have to go further afield before our clients see any game. It is going to be hard work.”

Bill stomped off to see his mechanics service the Cruisers. Lara turned to Maria, who shrugged and sighed.

“There's a big increase in poaching this year. We found elephant carcases everywhere. Machine gunned indiscriminately. They haven't only killed the tuskers – they take out whole families and juveniles. Threatened elephants are dangerous. When we did come across a big herd they were aggressive and we had to drive away very fast.”

She smiled at Lara.

“Well I'm glad to see you – that bad boy Jason will be, too.”

Jason, however, didn't seem as pleased to see Lara as she was to see him. While she was bursting to tell him about her exhibition, Jason was more reticent about his summer. He had learnt a great deal at Hluhluwe with the rhino project but it seemed to have congealed in him rather than opened him up. He said he was pleased that Lara had done well at the exhibition but he didn't want to talk about her commission at the bank.

“How are you going to manage to paint and do the work we need you to do here?”

His words made Lara's chest constrict.

Jason's not my boss - she thought angrily, Bill is okay with how I arrange my time. Besides I am a painter – it's what I do! It’s what I am.

A dull sense told her that Jason didn't much care what she was or did. With that realisation a hard ridge of resistance grew inside her just as, outside the camp in the shrinking river, a band of rocks was being exposed.

Lara and Jason still made love or, as it was beginning to feel to Lara, they had sex. It was more businesslike, over sooner and less satisfying. Lara began to understand that without love and consideration the sexual act didn't amount to much and was quickly forgotten. It was jarring to hear a noisy drunken group of men and women guests at the camp bar laughing and teasing each other about 'ball-breaking nymphomaniacs’ and men with ‘little dicks'. Lara was quite certain that, as a woman and a lover, she did not fit into any category.

A plump white envelope arrived at the camp for Jason.

“Stuff about Hluhluwe,” he said casually and took it away to read it.

Another one, fat as a small pillow followed.

“Pwah! Something here is a bit scented!” Bill said, handing it over.

The grass had died away on the nearest plains and the mupane trees had suffered heavy depredation by elephants. The antelope had moved on in search of new pastures. Bill called in a pilot who made a reconnaissance flight over the park and located more antelope further to the north-east. After consultation with the camp team, Bill sent Jason and Lara out together to explore new game trips that might make it possible to take clients closer to the ever-diminishing game herds. The weather was unpleasant and cold, the sky concreted over with stiff grey clouds, a spiteful wind flapped about, blowing spirals of dust and grit into their eyes. The wind and the Cruiser with Jason and Lara in it were the only things moving in an empty and deserted landscape. There wasn't even sufficient fresh animal dung to attract dung beetles. Without insects there were fewer birds. It was a dismal trip. Jason and Lara hardly spoke to each other. Their words would make too much noise in such an empty world. Soon after midday they parked out of the wind in a sheltered gully to brew some tea and eat sandwiches.

“Let’s take a walk – I need to stretch.” Jason said after half-an-hour. “We'll have a look around from the hilltop.”

Leaving their vehicle they walked up onto the crest of the hill above and raised their binoculars.

“That's a vicious east wind – nothing is likely to scent us from that direction – or hear us either.” Lara said pulling her jacket shut.

There was a sudden rigid alertness in Jason.

“Quick, Lara!” he hissed, “Get down flat on the ground,” and he too dropped down beside her.

“It’s poachers, Lara! I swear to God there's a least fifty of them all loaded up with meat and ivory. They are trekking south-east. If they see us we're dead. We can outrun them in the Cruiser but they'll have long-range bullets and AK 47s so it will be a risk.”

Supporting themselves on their elbows, they looked out at the distant line of men. Against the dull sky, a long line of misshapen black silhouettes trailed slowly across the high ground to their east, some 50 metres distant. They humped great burdens on their shoulders. Some carried loaded litters between them.

“They're moving away from us, thank God!” Jason said.

“You're right – there's forty-three that I can count.” said Lara, “but some of them are very small - just children – I think. There are about six men with elephant tusks. The guys at the front and back of the line have guns and aren't carrying anything.”

“Bastards! They go into isolated villages and get the old men and the young children to porter for them. Sometimes the villagers benefit from the poaching – get some meat maybe – but these kids and old men will walk 100s of kilometres and then have to walk home again. I expect there will be lorries waiting for this meat where the road enters the south-east of the National Park.”

The poachers moved very slowly. They were not expecting to be seen and fortunately for Jason and Lara did not bother to look around themselves at all.

“We're bloody lucky!” Jason said, “They’re not doing any more poaching so they haven't sent out scouts to check out the bush.”

“I expect they know they've driven everything away that they haven't killed.” Lara said.

Lara admitted to herself that she was afraid and fear was enervating. It was strange how fear felt like boredom. She would remember this time years later when boredom and fear seemed the total of her experience.

The poachers trudged on. It was an hour before they vanished from view and another half-hour before Jason risked driving their vehicle out of the gully and turning it for home. They had to race back to arrive at the Park Gate before sunset. The Cruiser jolted and bumped. Lara and Jason did not speak. They both had to concentrate on the road. Jason, in order to not damage the Cruiser, and Lara, so not to be flung about and be herself damaged.

Bill was stony-faced when he heard their news. The camp guests, nervous and thrilled. The necessary action was taken and the poachers were met by Game Guards when they reached the South-Eastern Park Gate. The haul totalled twenty boys, nine old men, some rotting game-meat, three poachers and the six ivory tusks. A number of the poachers had escaped. Most of those caught would hang around the Gate under police guard for some weeks and then be allowed to drift home when there was no more food.

The whole business took up time and energy. It was several days later than scheduled that Bill and Maria sat down with their camp staff to discuss their plans for the coming month.

“Ah, Jason.” Bill said, putting on his reading glasses and taking his pen from behind his ear. “We've received this application for work from um – from Leone Cilliers, your friend from Hluhluwe Game Park. She wants to come here next summer to work.” Bill looked at Jason over the top of his reading glasses. “You know we have a full team complement at the moment, don't you?”

“That's okay, Bill,” Lara said and coughed to clear her throat. “I'll be painting full time next year so I won't be coming back -” She looked at Maria. “I don't think so anyway - sorry Maria.”

Close Excerpt

The Shaping of Water

BY RUTH HARTLEY

Excerpt

12

CHOICES

“I don't think I believed that the lake would actually ever come into existence. That weekend that we all drove down to the valley was such a strange time,” Margaret said.

“When I saw the unfinished dam wall it looked as if it was being broken down, not built up. It was just a row of giant teeth sticking up in a random fashion across the gorge. The water looked so far away and insignificant — no bigger than the earth dam on the farm. I really didn't believe it would amount to anything much — nothing like this!” Margaret gestured at the lake before them as it lay glimmering under a glittering sky. “All that stuff about there being nothing in the valley except tsetse fly — I don't think I believed it. Nothing seemed real to me. Least of all that there would one day be a dam. It all seemed impossible and unlikely, and yet — here we are,” Margaret finished.

“I always believed in it,” Charles laughed. “All those workers slaving away under the tremendous heat. What an achievement! All those hundreds of cement lorries churning up the dust on the escarpment road with poor old Steve trying to overtake them in our terrible old pick-up when he couldn't see one yard ahead.”

“Mmmh — I was scared stiff all the way. The heat was unbearable, I thought I would suffocate from sweat and thick, sandy dust — and then when we got to the Kariba Heights Hotel and you had to rescue me from those Italian workers — I wanted to die!”

“You were so young and innocent — Steve and I didn't realise you had gone into the bar alone and the Italian men obviously thought you were — uh — a — well. We were pretty green also, Steve and me!”

“Really!” Margaret thought for a moment then smiled. “Of course that's what happened! What a fool I was — I had no idea then what a prostitute was, never mind that they lived and worked at Kariba. Is that why you decided to make an honest woman of me that weekend, Charles?”

“Something like that — something like that,” Charles said. “I just wanted to keep you safe for ever — and to keep you all for myself too, before Steve decided that he was going to have you. Darling — I have finished my beer — let me get you another gin.” And he bent and kissed her forehead on his way into the kitchen.

Margaret found herself fretting. When Charles returned she studied her drink, glistening temptingly in its tall glass while the ice clinked and the lemon fizzed and spun, then she turned to him again, wanting to be reassured.

“Charles — did we do enough? Did we try hard enough? Could we have done better? Politically I mean — and also as people?

Sometimes I am so ashamed to be Rhodesian. How did we fail so badly?”

“Of course we didn't do enough! Nobody ever does,” Charles answered, glancing at Margaret and then falling silent for a few moments.

“Could anyone have changed the course of politics in Rhodesia? I don't know. I don't think so. You and I were caught between those whites who would not contemplate a future shared with black people and those who insisted on full rights for blacks at once.

“I'm not black — if I was — maybe I would have not compromised either. I don't feel any sympathy for white people living in Africa who think they can deny black people votes for ever — or even for the immediate future. I have no sympathy for Jacob either — joining an organisation that was ready to use bombs. I do believe that communism is a dangerous threat to the liberty of us all in the west — at least we have freedom of thought and speech.”

“Do we?” said Margaret very quietly. “Do we? They don't have it in South Africa.”

“True,” Charles acknowledged, “but Margaret — one thing I know — we don't escape the consequences of our actions — whatever they are — there is still a long way to go before anything is resolved in this part of the world.”

“It's also been going on for ages,” said Margaret, wanting everything to be better tomorrow just this one time. “Remember the Mau-Mau uprising and in the end in spite of everything, Kenyatta still becomes the president.”

They fell silent, each occupied with their own thoughts.

*

The fifties, when Margaret was at school, were also the years of the Mau-Mau uprising in Kenya. The long and bitter fight for human rights against cruel oppression in colonial Kenya was seen in white Rhodesia as an atavistic murder spree, inflicted only on white people by a savage and primitive minority. The nineteenth century rebellions in Rhodesia against white domination were long over but once Rhodesians heard of the Mau-Mau, a prickling sense of fear and guilt kept everyone looking backwards over their shoulders. At school increasing levels of hysteria and prejudice on all matters to do with race and politics led to arguments and persecutions among the girls. School meals at the boarding house were served up by African waiters who also did the domestic work and gardening. To the white schoolgirls, they were nameless, worthless skivvies who were mostly ignored, but were verbally abused whenever their presence brought them close enough.

“While I am a prefect no one on my table will call a waiter ‘kaffir’.”

The words came out clear and firm. Margaret's elocution was good. She was well-taught. Still she was surprised that she had managed to speak those words and that she was audible. She also expected an immediate rude response but the girls in her charge were taken aback. So surprised in fact that no one questioned her or challenged her, or insulted a waiter while she was on duty again. Margaret would be called a 'kaffir-boetjie' behind her back from now on but she had realised, in that instant when Leonie jeered at Simba, that she had to take charge or give up forever and listen in misery to the daily diet of racism that was dished out to the men who served her food.

Simba, a tall ungainly man with huge feet, was standing at Margaret's table holding a tray of banana and jam sandwiches when Leonie, a child of fourteen, said to him,

“Hey kaffir — take the dog food away!” Then she had laughed.

Simba wanted to kill Leonie. The blood roared in his ears. He turned and walked back to the kitchen, blind and deaf with rage. Afterwards he was not sure what he had heard Margaret say though another waiter, a young boy called Thomas who was the same age as Margaret, said it was true. Simba did not care anymore. He was filled with hatred. It was devouring him. At night the girls above in the dormitories heard him shouting at the other workers in the servants’ quarters. He raved in ChiShona about raping white girls. They understood the hatred in his voice but not his words, nevertheless it stopped them sleeping. Simba knew he frightened them. He knew if they complained about the noise he made he would lose his job, but he was growing tired of the sickening taste of bitterness. He would leave his job in the government school anyway. He would go to the mines of the Northern Rhodesia Copperbelt. They said the money was good there. They said the white mine-workers were the worst sort of racists — cruel bullies — all 'boers' from South Africa but at least they would be men and he would not be ashamed to want to kill them.

The ill-treatment of servants took place at school meals every day. It continued at every table except Margaret's until she left school two years later. Then of course it began again and increased in viciousness. That was the year the right wing political party of Ian Smith began its campaign with a poster asking:

'DO YOU WANT YOUR DAUGHTER TO MARRY AN AFRICAN?'

It was printed over a photograph taken at an International Girl Guide Jamboree that showed children of all races running in a race together.

Nothing in Rhodesia was changed by Margaret's action except herself. She had crossed a line. She did not think that her action was political. She was not political. Politics was for men. Margaret had only done what her father would have expected of her. She had insisted on good manners. It was important to treat people well and with respect, especially if they had less power and less of everything that she did. It appeared to Margaret after that school meal, that the speed of political change in Rhodesia quickened and moved dramatically to the right. It seemed to her to be moving more and more towards a solution like that of South African Apartheid. Since that evening, nothing offered hope.

*

With a sigh, Margaret returned to the present, to the warm evening and the sound of the lake and Charles by her side. The boys, Michael and Richard, were asleep on the bunk beds, tired after a day spent swimming and fishing and scrambling along the shore in search of legavaans, snakes and scorpions.

It was more than five years since Rhodesia under its Prime Minister, Ian Smith, had made its Unilateral Declaration of Independence. He had decided only six months before to shut the borders between Rhodesia and Zambia because, he said, of the support offered to dissident political groups like Joshua Nkomo's ZAPU by the President of Zambia. Margaret turned to Charles.

“Have you any guesses about what will happen next in Rhodesia?”

Charles very slowly shook his head once, twice, then again.

“Bloodshed,” he said quietly. “There will be bloodshed.”

Below Charles and Margaret the waters of Lake Kariba chewed ceaselessly at the shoreline, gnawing and regurgitating, smoothing and scouring, claiming an empire, reshaping an ancient geology with a million new forms of life as it explored the dam's creations of mud and crevice and beach and depth. On and on and on went the moving waters, invading, colonising, subjugating, populating and changing forever the largest valley in Africa.

*

Below the dam wall, in the deep cool shadowed night of the Kariba Gorge, there were a few quiet splashes on the river, a fish perhaps taken by a giant orange fishing owl; a stalking crocodile sliding its snout up onto the bank as a duiker or bush buck made its shy, delicate way to the water's edge for a drink. The shrilling of the cicadas seemed to make an unending chain of noise but to any experienced listeners in the bush there were momentary missing links in the sounds. There were abrupt silences where suddenly stealthy rustles could be heard as they shifted carefully onwards until the next cicada fell silent and the last one joined its racket to that of its fellow creature all over again.

Simba's young friend Thomas and his cousin Jonas, were making their way northwards into Zambia. They had come across the Kariba gorge to find the ZAPU encampments and join the liberation struggle. A Tonga fisherman ferried them over the Zambezi in his bwato. The fisherman was wearing a traditional mubeso loincloth over his deformed and rigid hip. His teeth were filed into points. Around his neck was a mpande shell on a beaded string. He said that long ago a hippo cow whose path he crossed had almost broken him in half with one bite. He always laughed when he told this story. He had been young and foolish then but he had lived. He liked to be in his bwato as he found it hard to walk. His name was Mafwafwa: the one who has escaped death.

At the other end of the lake in the rapids of the headwaters of the dam, Simba was crossing back into Rhodesia with a group of guerrillas. They too were helped over the rapids by Tonga fishermen in their bwatos.

Simba had been recruited by ZAPU cadres while he was living in the Copperbelt. He had not wanted to join ZAPU but his rage against whites had never abated and he had not been able to keep any jobs in Zambia. The cadres took him to Tanzania and from there he was taken to China for three months' training. He was an intelligent, independent and argumentative recruit but he had good reason. The Rhodesian Security Forces were well established in the bush in Hwange district south of the Zambian border. Their kill rate for ZAPU insurgents was very high. Simba said that ordering regular army-style groups of the liberation army unsupported by the local villagers into this area could not win the war and they would all be killed. He and others guerrillas who said the same thing were right, as their leader, Herbert Chitepo, back in Lusaka would eventually have to admit.

Simba was going to his death at the hands of the Rhodesian soldiers. Before he died however, Simba would become a legend for his fearlessness and his rage.

*

Charles and Margaret and the two boys slept well that night. The weather was not too hot and they were at peace with their lives for the moment. Charles as usual got up at sunrise but half-an-hour earlier, a village Headman was banging on the door of the Siavonga Clinic. Before the bemused doctor from the power station construction company understood why he was wanted, he was being rushed into the bush in the direction of Sinazongwe. A group of local Tonga villagers had accidentally walked into the land mines laid around a ZAPU camp. There were four dead men and one who, apparently uninjured, was in shock and dying and would not survive the trip in the Land Rover back to the clinic.

No one ever did explain to anyone's satisfaction, who the land mines were set to trap and why.

Close Excerpt

The White and Black Blues

BY RUTH HARTLEY

Excerpt

RUZAWI

I was inside the wrong outside. The idea struck me while Dad was boozing in the Ruzawi Clubhouse bar and I was lounging in the shade of a lucky-bean tree with Ted.

“Your Dad’s a waste of white skin,” Ted said.

He flicked his cigarette next to my bare toes and watched my expression as he ground the stub into the red dust. No way could I rescue that stompjie to share with Patrick. Ted had been Dad’s farm assistant until he took him on in a shouting match. Bad call. Dad is the absolute best champion shouter. He can outlast a thunderstorm and still shower you with spittle. Ted got the sack and Dad ferried him to the clubhouse so he could cadge a lift back to the city.

Dad wasn’t much good as a farmer but did the colour of his skin matter? Most of his visible bits weren't white but the sour lemon yellow colour of the first leaves of the tobacco harvest. The edges of him, fingers, teeth and face were the rusty brown of the last tobacco leaves that his black labourers hand-picked. Dad didn’t need much skin. He was a little bloke with a chesty cough and wire coat-hangers for shoulders bent round a shirt pocket rigid with cigarettes.

Patrick’s father, the Reverend Nkole, was the opposite in size, colour, and big-heartedness to Dad. He was a pastor in the Tribal Trust land where Patrick went to the local mission school. At weekends Patrick did odd jobs and skivvied for the Ruzawi club manager. He couldn’t swim, play tennis or come into the clubhouse because he was just an African. I was with my Dad in case he got plastered and I had to drive him home. I was too young to have a driving licence but I did it anyway. I could swim if I wanted but there were usually only little kids and their mums there and that embarrassed me.

It’s obviously better to have a white skin on a Rhodesian farm but I wondered how skin could be wasted on anyone. It pretty much fits unless you are so old that it’s loose and scraggy. My Mum‘s skin is soft and sags. When she's tired makes me afraid she'll burst into bits. I personally don’t have spare skin. Like Dad I'm short, bony and sharp-featured. My skin is brown with scabs on my knees and bruises on my arms. I don't think my skin defines me though – like – did I choose it? I bet if Dad was a snake and shed his skin it would still smell of sweat and beer. If I was a chrysalis I wouldn't be a butterfly I'd be a bug that had outgrown its case. I'd like to be a flying insect but it doesn't look as if I'll get bigger anyway. If I cut my skin it hurts and I bleed. One of our workers ripped the skin off his leg on a ploughshare. He yelled but my Dad swore at him and he went quiet. I stared at the blood running over his foot and between his toes. Underneath his dusty black skin his flesh was exactly the same pinkish-red colour as my grazed knees.

Ted got a lift to town with a farmer who needed to buy equipment. He chucked his bag into the back of the pick-up, clambered in and was gone without even saying tot siens. I wandered into the clubhouse. Dad wouldn't be leaving any time soon and Patrick was busy scooping leaves from the swimming pool. An old piano, lid open, stood by the platform that served as a stage and band stand. I tapped at the keys softly. One or two only clacked and others sounded wrong. We don't listen to music at home. Mum has forgotten how to play Beethoven's 'Für Elise'. Dad has a record of something he calls 'Swing' by Harry James which I mustn’t touch. At boarding school in the free hour after prep, students sometimes bash out a mad version of Chopsticks. It sounds great. I would love to play the piano but no way will I admit it to anyone and especially not to Dad.

Dad was in a bad mood because of drink and the fact Ted had gone. He shouted at me for the first half of the drive home. I was a waste of space he said. I was always wasting time he said so natch I told him what Ted had said about him. Of course he slammed on the brakes and told me I could bloody walk the 5 miles home. He clouted me across my ear for “good measure”, something he often said when thrashing me.

I waited for the car's dust trail to settle before I followed. It was still very hot and I was majorly thirsty but I didn’t dare hang about. It gets dark really fast in the bush and though the farmers say they have shot all the lions you never know for sure and leopards can be extra sneaky animals and appear just where you don’t expect them.

The sky was turning grey and I had goose pimples and a prickly feeling down my back when I heard a car behind me. I wasn’t sure whether to hide or not. It would be humiliating to have to explain why I had been dumped on the road. From the racket the car made I reckoned that it was a crappy old banger and probably belonged to a local African. Africans can sometimes be really kind, especially to kids, so I stood up and looked hopeful. It wouldn’t do to arrive back home too soon but I could wait in the tractor shed till I judged it was about the time it would have taken to walk there. The car stopped, my friend Patrick waved out the window and his father, the Reverend Nkole, climbed out and wrapped me in thick tweed-covered arms. Now I was embarrassed because I sussed that the dust from Dad’s car had got smeared on my face with my tears and boys my age aren’t supposed to cry.

“Dad's punishing me,” I explained when Reverend Nkole offered me a lift. The Reverend considered.

“I'm visiting the next farm. We’ll drop you home afterwards.”

At the farm compound there was a celebration going on and the Reverend blessed everyone. The women brought orange squash and bread buns for the Reverend and gave some to me as well though not to Patrick. I suppose it was because I was white that I counted the same as the Reverend to them for food, but it felt wrong. Patrick and I are the same under our skin so I shared my bun and drink with him.

I began to feel happy. The workers clapped their hands, swayed their bodies and stamped their feet in rhythm to the drumming. Everyone sang. Everyone knew how to fit their voices together in different ways that matched, even when their voices were higher or lower than each other. I don’t know how to describe what they did or how they did it but I could hear that it was simple, and easy, complicated and right. I began trying to rock my body and shuffle my feet along with everyone there.

“Shame.” Patrick said, “White people can’t sing and dance like us Africans.”

I knew why he thought that. White people don’t sing and dance as they work.

“I’ll show you.” I answered and we laughed and together started to stick our bums out and slap our feet onto the soft dirt in a sound and rhythm pattern.

Close Excerpt

When I was Bad

BY RUTH HARTLEY

Excerpt

1

ARRIVAL

On April Fool’s Day 1966 I arrived in London.

The strangers who were my travelling companions from the Dover ferry had dozed in silence all the way to Victoria Station. When the train stopped it jolted them from their seats and into such swift action that the platform rapidly emptied. I had been so successful in not drawing attention to myself on the journey that none of the passengers even glanced at me as they disappeared off to their own lives. I felt I was being abandoned. I didn’t have a life waiting for me. I might be carrying a life inside me and I was certainly hoping to find a life, but what kind of life did someone like me deserve? I was someone who had secrets. I was someone whose actions defined me as bad.

Where were the public payphones? Exhausted and cold, I didn’t know where to look. The walk past the stationary train seemed unending. The ridged handle of my leather suitcase cut into my frozen fingers. It was much too heavy. There weren’t any porters that I could see. I wasn’t used to carrying my own luggage and nobody offered to help me. In Rhodesia and South Africa there had always been plenty of black porters on the stations. I began to regret that Alan Wilson and I had swapped suitcases. He wanted my larger lighter case for his plane journey to Israel. I took his smaller heavier case to be helpful and so I could hold onto something of his. The case was my mascot. It was a connection with my vanishing past and the political training Alan had given me. When we made the exchange back in Natal, I hadn’t imagined that I’d have to use it to travel to Great Britain.

“The revolution will take another 10 years,” Alan had said to me at about the same time. “It can’t happen any sooner.”

I must have nodded my head slowly while I considered what that meant. I had no idea what shape a revolution might take or how I could recognise it, but it was obvious that Alan and I couldn’t make one on our own. There didn’t seem to be anyone left in South Africa who wanted racial equality and freedom. They were all in prison or exile or dead like Suliman Saloojee. Since his estimate of how long the revolution would take Alan had gone to Israel to wait for it and I had moved to Cape Town. Now I, too, was going into exile and not because of any brave political actions but because of sex and love and because I was bad. The South African revolution might now be only 9 years away, but I wouldn’t be there waiting for it.

The Spiral-Bound Notebooks

BY RUTH HARTLEY

Excerpt

APARTHEID

the thick green grasses above

the sweating vlei looking for dead bodies.

Under some compulsion

I went out among the rich fields

where the song birds spill their sweetness

among the choking scent of lilies. ...

I wrote this while at the University of Cape Town and living in Baxter Hall during my first year in South Africa. Cape Town was very beautiful but it was not long after the 1961 Sharpeville Massacre. As a child I had fallen into a vlei (a seasonal pond or marsh) of stinking mud when I went to pick arum lilies. "Lilies that fester smell much worse than weeds." Sonnet 94 by William Shakespeare.

The Love and Wisdom Crimes

BY RUTH HARTLEY

Excerpt

"Someone close to them will inevitably be a police informer," Dan warned Jane. "See if you can guess who it is. Find out their name. Don't draw attention to yourself; Just don't get involved in political discussions while you are there!"

She did not get to ask Dan about Marxism and love because the next day at 10 o'clock in the morning, Dan was arrested by Special Branch.

...

Jane had grown up into the landscape of South Africa as it was being destroyed by apartheid. She had grown up into a landscape of hearts broken by apartheid and now she knew her own heart was breaking. Dan was going to a secret destination and she could not expect to hear from him again. He had said that he would not be able to stay in touch. Perhaps he did not choose to be in touch.

Jane thought how her life was fragmenting, how she did not know the ends of anyone’s stories and maybe never would. She thought how she could not know the truth about anyone now or ever. She did not know the truth about Dan.

Close Excerpt

When We Were Wicked

BY RUTH HARTLEY

Excerpt

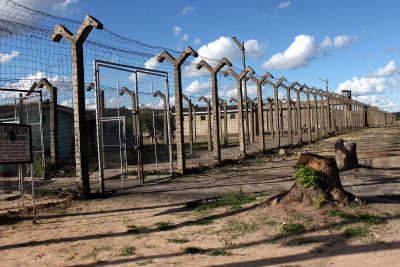

Not in Front of the Children - A Memoir

Every fourth Sunday after church Mum drove us to Chikurubi prison. I didn’t know why we had to wait outside it in the car. I didn’t know it was a prison. Neither did my sister. I was five. She was three. I knew black people went to prison. I didn’t know that white people did. Chikurubi Prison stood in the middle of nowhere, a flatwalled, introverted fortress with guns pointing into its own guts. Its brick bulk was too solid to ignore and too dull to remember. Mum drove there in silence. She parked on the dirt forecourt, wound the windows almost shut, got out and locked us inside. “I won’t be long,” she said, a small crease between her eyebrows. The bright sun was hard on her face. She turned away and disappeared through a small opening in a huge double gate. Around us the flattened valley was cleared of trees and its grass cut short to a stiff ankle-scratching yellow-brown length. The heavy, hazy midday sun pressed down on the stifling car while around it cicadas shrilled like boiling kettles. We may have sweated and squabbled in our Sunday School clothes, but I remember succumbing to lethargy and sleep rather than fractiousness. Mum was always gone exactly half an hour, after which we went home to roast meat prepared by our African cook and carved by our frowning father while Mum smiled and smiled. This strange gap in our Sunday was never commented on and had no connection at all with the rest of our lives.

...

My sister and I often squabbled, but Uncle Bruce’s first appearance in our home a year earlier occasioned one of our fiercest and most physical fights. Bruce was Mum’s younger brother, a bespectacled adult in the body of an underfed adolescent. We didn’t notice his height because we were even smaller. Despite his minimal size, Uncle Bruce managed to smuggle a ginger tomkitten right past our watching parents. It was a gift that didn’t divide in two. Skilled parenting prevented the kitten’s early demise and us from suffering terrible lacerations. We still fell on each other over its name until Mum recombined our opposed choices of Jackson and Peter, suggested by the brand of cigarettes in Bruce’s shirt pocket. Peter Jackson, the tobacco-coloured kitten, remained a thorny problem. Kidnapped by Bruce from a feral cat family, he soon effected his escape. I don’t think my sister and I minded much. Peter Jackson was hard to catch and impossible to cuddle.

Uncle Bruce visited at weekends, bringing other gifts. While he was with us, the grown-ups said little to each other and told us off more than usual. Once he brought some surprisingly gorgeous doll’s clothes. Mummy, calm as ever, asked him where he “found” them, then quietly put them away “just to keep them safe”.

The next time Uncle Bruce came by, my sister and I were halfconscious and too ill to scratch our measles pustules. He promised to babysit whilst Mum went to the chemist for medicine. When she returned we were alone. Uncle Bruce had been through the bedroom cupboards, found Dad’s illegal pistol, a souvenir from his war service, pocketed it and disappeared.

...

As soon as my sister and I recovered from the measles we were separated and sent away to live with other families. We returned home many weeks later in a state of shocked alienation to find that Granny Emma had come to live with us. Mum and Uncle Bruce were her children. Dad had built her a small round room with a grass roof behind our house. Granny Emma smelt of the camphor wood wedding chest in which she still stored her clothes. She crocheted all the time making doilies, tea cosies, and covers for toilet paper rolls. When Granny Emma was surprised or amused, she hooted like an owl. My sister and I found her fascinating. Dad found her annoying. “Your Granny deserves respect!” Mum explained with a smile. “Her family were very poor German settlers. She grew up without shoes and had to leave school at at fourteen.”

“Woohooh!” Granny Emma hooted when I made a drawing. “You’re artistic! Just like Bruce!”

I wasn’t sure I wanted to be linked to my uncle. By the time I was nine, I knew he was in prison, though not why. Besides, the proof of Uncle Bruce’s artistry was a charming little story book he had made about my pretty sister, and I was jealous.

Bruce painted a shop sign for my mother’s farm store. It showed a queue of unsmiling Africans waiting for it to open. There was no sunshine in the painting, nor, I guess, in the prison workshop where Uncle Bruce was being rehabilitated, ready for his release and deportation. He had one whole year to wait. I was thirteen by then and at boarding school. It was judged I was old enough to hear some of the truth. I sat down in my uniform on a school chair while Mum told me about her brother. Uncle Bruce was a South African-born criminal who had served his time. The police would escort him on the train to the Rhodesian border. Then she would travel with him to a Christian organisation that would help him find work in a country he no longer knew.

My mother’s brother was a double murderer. That awful knowledge was a bloated secret inside me. It was not a secret to anyone else in Rhodesian society. Eventually I asked Mum what Bruce had really done and she told me the story in bits and pieces whenever we were alone.“Bruce was a wild boy … it was the Second World War … at sixteen, he enlisted in the South African Army and was sent to Italy … became a dispatch rider carrying messages between the British front lines. It was very dangerous work … Bruce was ‘Mentioned In Dispatches’ for his bravery but as always, he was out of control … he got into a fight, had a duel with another soldier and shot and killed him … too young to be executed by a firing-squad, Bruce was brought back in chains to a South African prison. Conditions were so terrible he lost his teeth and became very ill.”

“Granny Emma began a long campaign to get him pardoned on account of his youth and bravery … finally she saw General Jan Smuts who did pardon Bruce … that is how he was able to come to live near us in Rhodesia.”

For almost four years Bruce wasn’t mentioned in my hearing. There were other heavy drinkers in the family. Pregnancy and madness became the current family problems, not murder.

Then it was Christmas Eve and suicide time. We were gathered together in the farmhouse sitting-room when the phone rang in the passage.

No other telephone sounds like an old country phone. Ours was a wall-mounted, black metal box with brass hooks to hold the receiver, a stiff noisy dial, and a crank-handle at its side. All the local white farmers shared the same exchange. Three turns of the crank handle, three rings and anyone could pick it up. More rings and it was the central exchange calling. If it rang it was either gossip or very important. We always jumped up and answered at once. Christmas is also the season of thunderstorms and interference on the phone line. We heard crackling and shouting. My sister came back, her voice high-pitched in panic. “I can’t hear! It’s from South Africa!”

Mum took over. The crackling and the distant thunder increased in volume but those of us left in the sitting room heard her repeat odd words in her clear voice.

“BRUCE.”

“CAR.” Or was it “CARBON MONOXIDE.”?

“SUICIDE.”

My stepfather shouted.

“I DO NOT WANT TO HEAR ANOTHER WORD ON THIS SUBJECT.”

Granny Emma was absolutely still...

Close Excerpt

The Colourless Child

BY RUTH HARTLEY

Excerpt

The Secret Meeting

1 - Cheelo's Skin

My skin is transparent and doesn’t protect me from the sun. That’s because my skin has no melanin (pigment) in it. My mother tells me I am a colourless child.

My skin is a monster problem for me. I think about it all the time because it stops me from doing things. For example, Mom says I can go for a swim this afternoon, but only when it’s cooler. Today is weird anyway because the whole family is going to a restaurant and my stepsister Natasha has been told to babysit me. That annoys both of us. I’m a good swimmer and we have a swimming pool at home. Natasha wants to be with the grown-ups not her kid stepbrother.

“Eveline needs you to look after Cheelo.’ Carl says, giving Natasha one of his looks. She’s his daughter, so she is used to them. Carl is my stepdad and I can tell the rest of that conversation is not for my ears and they’ll carry on talking somewhere else. Natasha’s eyebrows go up then down and it’s her turn to give me one of her special looks. She practises doing them in front of her mirror. The trouble with my skin is that everybody looks at me in funny ways because of it and now my family is doing it, too. It got worse when Carl decided to stand for the Republic’s parliament and my Mom (Natasha calls her Eveline) got all nervous and jumpy. Mom thinks Carl and his friend, Mr Saviour Kasuba, will get lots of votes, so that’s not the problem. She says the Republic needs a better government than it’s got now. Mr Kasuba wants to be President and he wants Carl to be his economics minister, but here in the Republic anything can happen, even to people who have normal-looking skin.

You wouldn’t believe it but my ‘genetic’ father who I never see (that’s what I call him because he disowned me because I am a colourless child) has arranged a secret meeting for Mom and Carl at this restaurant. I’m not supposed to know that it was my father who arranged this meeting, but I heard Mom say his name on the phone and then minutes later she said that we all must go out. I’m not deaf, I’ve got no pigment in my skin, but that doesn’t affect my ears.

If you don’t know what pigment is, I’ll explain. My Mom is African, and her skin is dark like my ‘genetic’ father's. They both have melanin in their skin. My stepdad is half-African and half-Jewish, so the melanin in his skin is not so dark. My stepsister, Natasha, is a quarter-African and a quarter-Jewish and her other half is white African, so she is lighter than all of them, but she still has got melanin in her skin that gets darker when she’s sunburnt. I’m different. I’ve got no melanin and that means I’ve got see-through skin, so the sun just burns me right through it. Melanin is the pigment that protects humans from the sun. Most people have it, but I don’t. If that’s not bad enough, wait till you hear the rest of what it’s like to be me!

Anyway, my actual ‘genetic’ father (his name is Henry Moyo) has phoned Mom and Carl. He wants them to meet him at this apamwamba (that means expensive) restaurant, but while this election is on my Mom won’t let me out of her sight, so I have to go along, too. Natasha must come to keep an eye on me, though neither of us is allowed to listen to what the grown-ups will say. No wonder Natasha is cross. She’s not quite as grown-up as she thinks she is, but she likes to know everything.

‘What do you think it’s about?’ I ask Natasha.

She answers quickly because she’s annoyed and then she’s sorry she said so much.

‘It’s about you, of course! I mean Eveline and Carl think you would be safer in the Old Kingdom instead of here during the elections and that’s why they are going to talk to your father. They need his permission.’

That makes me feel horrible and afraid.

‘Why?’ I say trying not to cry, ‘I don’t want to go anywhere – I want to be at home. I hate my genetic father and he hates me!’

Natasha looks guilty and upset.

‘It’ll only be for a few weeks, Cheelo, and I’m going with you as well – I’ve got an art course at a summer school there, so we’ll be together. We’re going to stay with my Auntie Hannah.’

I might need to have Natasha on my side. Now she’s feeling bad I’ll see what else she can find out and tell me. I sniff and rub my eyes and look miserable.

‘Please, Natasha – can you find out what’s going on when we are there? Otherwise, I’ll make a fuss about what you’ve said to Mom when we’re there.’

‘Okay’ she says, ‘I’ll try and listen to what they say, but you’ll have to pretend you don’t know anything.’

I know Natasha is just as curious as I am, but I have a bad feeling about what is being planned for me at this meeting.

Carl has arranged for his driver, Gideon, to take us all to the restaurant in our battered old four-wheel-drive estate. We drive through the customer car park at the restaurant and up to a private space under some big trees. Natasha clicks her tongue in disappointment.

‘Wezi, my art teacher, has some of his best paintings in this restaurant,’ she complains. ‘They’re very big and expensive – I wanted to see them. I don’t want to go in the back way.’

I know about Wezi. He’s a famous artist and Natasha adores him, but my Mom says he’s sick and shakes her head when she speaks about him. He’s got the kind of sickness that is scary for me, so I don’t want to have anything to do with him, but I’m not supposed to say that.

‘Park at the far end where the car won’t be noticed and drop us at that small back gate,’ Carl tells Gideon. ‘Henry’s meeting us inside.’

I can see that both Mom and Natasha wanted to go in at the main restaurant entrance, but there’s a very smart uniformed security guard by the small black metal gate who salutes us stiffly. I can tell Carl is impressed. As usual, Carl marches in through the gate ahead of Mom. As usual, it annoys her. The guard bangs the gate shut and then locks it. That makes me and Mom jump. Natasha is sizing up the place as we agreed before we left home.

My ‘genetic’ father, Henry Moyo, is sitting at a table under a gazebo roofed with yellow flowers. There’s another man with him in the shadows. Mom whispers to Natasha and points towards the swimming pool and changing rooms. I think my ‘genetic’ father is staring hard at me, so I turn away and ignore him. When Natasha and I come back from the changing rooms, the four of them have their heads together over a tray of tall glasses. We can hear their voices, but not what they are saying. It’s what Natasha and I expected. She strolls very slowly towards them, places her handbag gently by Eveline and asks if the two of us can have some cool drinks while she smiles and stares at my father and the stranger.

‘His name is Imran,’ Natasha tells me when she has strolled back looking casual and bored. ‘Carl was at university with him. He has a posh accent and is dressed in an expensive suit.’

I don’t know how she knows about suits. Carl never wears one, but I can see that my ‘genetic’ father does.

‘I think he’s a spy from the Old Kingdom. I think it must be about the elections here,’ Natasha continues.

‘So, what does that mean?’ I ask, but Natasha just makes a face. She doesn’t know either.

After a while, my Mom’s voice gets shriller and quicker and I hear my name - ‘Cheelo’ – so I know I’m being talked about.

They all start talking at once. I feel a bit sick, but then I’ve eaten two ice creams. There seems to be no limit to what the waiters can bring us.

‘Call my phone!’ Natasha whispers to me. I do and the phone rings in the bag Natasha placed by my Mom. She races over, picks her phone out of her bag and hangs around the grown-ups so she can hear what they are saying.

‘Take your bag and your phone away,’ Carl says. Natasha glances at Carl’s face and doesn’t argue.

Natasha comes back and flings her bag down next to me.

‘That didn’t work,’ she says, ‘They were talking about right-wing terrorism and world domination plans – they say that the Republic is also targeted because of the elections. They didn’t mention you - only Carl.’

‘Why send me away then?’ I ask. Something doesn’t add up.

‘When we get home, I’ll see if anything has been recorded on my phone,’ Natasha says. ‘I shouldn’t have asked you to phone it so soon.’

‘You’ll tell me everything, won’t you?’ I ask Natasha.

‘Of course,’ she says, not looking at me.

We hang around the pool for another hour until the sun sets and I start to shiver. I go up to the grown-ups and tell them I’m hungry. My genetic father to my surprise immediately offers to buy Natasha and me hamburgers and cokes. That’s not bad and soon after we finish eating them, they stop talking and we all go home, but I get sent straight to bed because there’s school tomorrow.

‘I’ll tell you about this tomorrow,’ Natasha says, tapping her phone when Carl and Mom aren’t looking. Of course, she means tomorrow after school because she doesn’t get up early and so I must wait and wait. When she does tell me it’s very disappointing because the phone didn’t record much and it’s not easy to understand. It’s a mess, but this is some of what we can make out.

‘. . . many organised right-wing groups . . . Dark Web . . . aim to destabilise democracies and nations and then feed off the chaos that ensues . . . a small bunch of white supremacists from Southern Africa . . . grudge against the Republic . . . apocalyptic world . . . the Last Days . . . a special interest in our elections . . . cause riots and civil unrest . . . safety in the Kingdom . . . an intelligence deficit we can’t fill . . . important for us to . . . Cheelo’s safety . . . first . . . Natasha’s Auntie . . . stories . . . Hannah’s ex-husband, Don . . . complications . . .’

‘What has this got to do with me?’ I ask. ‘Why will Mom have to send me away – I don’t understand.’

Natasha looks at me and says nothing helpful. I do have some idea about it because of something that happened a while ago. We had a new worker who kept staring at me – that happens a lot outside my home - but this man was inside our garden, and he pounced on me and grabbed my hand with a grin.

‘Give me some of your fingers and I’ll give you very much money!’ he said. ‘Mr Carl is lucky because of you – he can win the election with one of your hands – just give me some fingers.’

I pulled my hand away and ran inside to my Mom. I was terrified and my heart was pounding. I went and hid in my bedroom and my Mom shouted and shouted at absolutely everyone she could see. I never saw that worker again, but if I think about what happened then I feel sick with fear. If my skin is lucky for some people, I don’t think it makes me lucky at all.