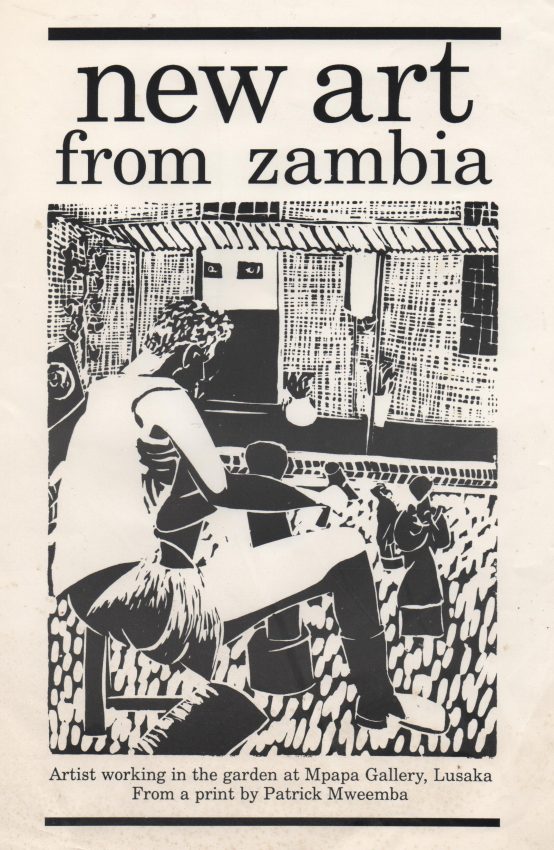

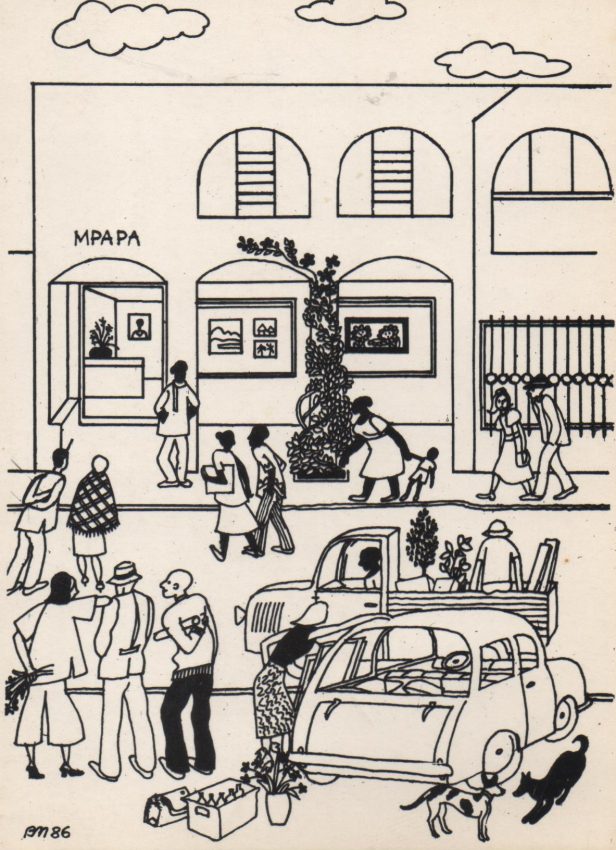

Mpapa Gallery, Women and Art in Zambia

In 1984 when I started working at Mpapa Gallery with Joan Pilcher, Cynthia Zukas and Patrick Mweemba, there were many women making art, but few were Zambian and none were black. Most women artists were the expatriate wives of businessmen, diplomats and aid agency officials. Colonial domination of Zambian culture before 1964 is one factor, but the reality is more complex and reflects the low status of both women and art in all of western culture as well as solely the British colonies. In this post, I want to explore some of the reasons for this misogyny and how it still needs to be changed.

Watercolours for ladies and fame for men

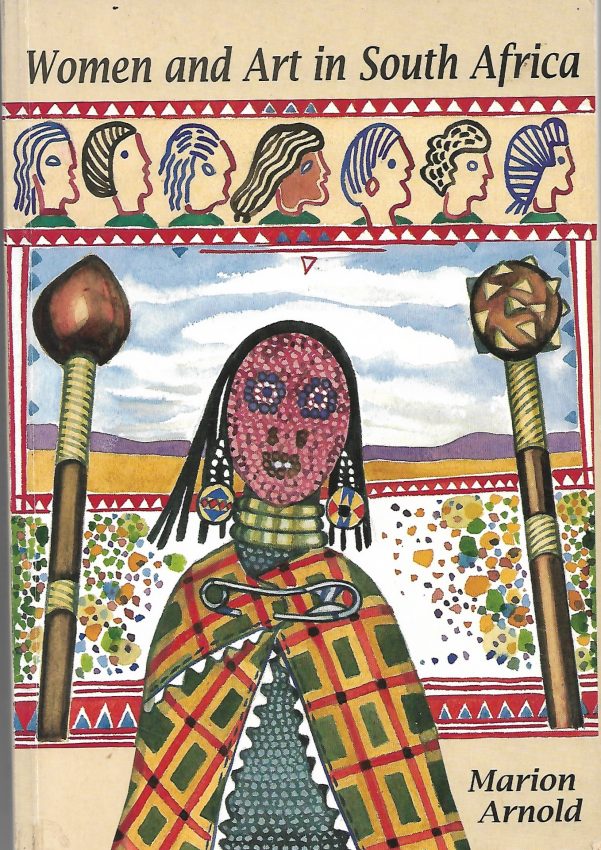

When I went to the Michaelis Art School in 1962 about 70% of the students were women, but the few men there were noticeable for their high marks and status. Schoolboys weren’t encouraged to study art, so these men had to be both passionate and focused. In contradiction, art was seen as a ladylike occupation for a girl who would inevitably marry and might need a hobby when her husband was busy. Women, however, were just as determined as men to make art and to make it well. Many women artists in the Southern African region fought apartheid and worked with black African artists as did Sue Williamson, Marian Arnold, Bente Lorenz, Cynthia Zukas, Helen Lieros and myself.

Every successful (male) artist was a genius

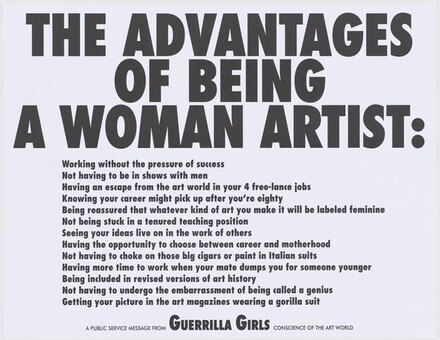

In the 1960s art history taught that great artists were male geniuses who died in poverty. Women took off their clothes to pose for men, but men didn’t pose for women. There may have been more women studying art, making art and teaching art, but art history was sexist and so was art education, career structures in museums and galleries, art journalism, the art market and art patronage and funding. Zambia’s art world at Independence exhibited all these contradictions, together with the problems of its own underdevelopment. It is illustrative that the art teachers at the Evelyn Hone College in those early years were mostly expatriate men, too. I had been active in the 1970s Women’s Movement and equal rights for women were important to me, but Zambia in those years was male-dominated.

Independent Zambia

Zambia had few men and fewer women graduates in 1964. Colonialism had given power and status to Zambian men, but not to women. Outside the Zambian family unit during that period, men and women worked and socialised separately and that reinforced colonial bias. Added to this was the existing lack of equality and opportunity for women everywhere in the world, which was inevitably magnified in a new country like Zambia. Zambia remained a unique case because it attracted expatriates who were dedicated to the idea of an independent and non-racial society. Cynthia Zukas and Bente Lorenz were already working alongside artists like the Zambian, HenryTayali, and the Minister for Culture, Simon Kapwepwe, to empower creative arts and artists. I had been at the London School of Economics in 1968. My politics like those of Cynthia and Bente were radical, not colonial.

Creative arts, race, class and gender

As the creative arts industry is always in flux it challenges class, race and gender. In a society where men are fixed in control of society, women will find ways to circumvent class, race and status. The same is true for any group of people excluded from power by race or poverty. To be human is to be a creative problem solver and the arts offers routes of resistance, escape and fulfilment. During Zambia’s first 30 years there was a fruitful collaboration between both black and white artists. It is exemplified by the ceramicist, Bente Lorenz, who during World War 2 had been in the Danish resistance, and who provided studio space for sculptors like Tubayi Dube, Masiye Mitti and Adamson Ngosa, while working with traditional female potters like Paulina Mubanga and Dervish Mvula.

Art, apartheid and war in the Southern African region.

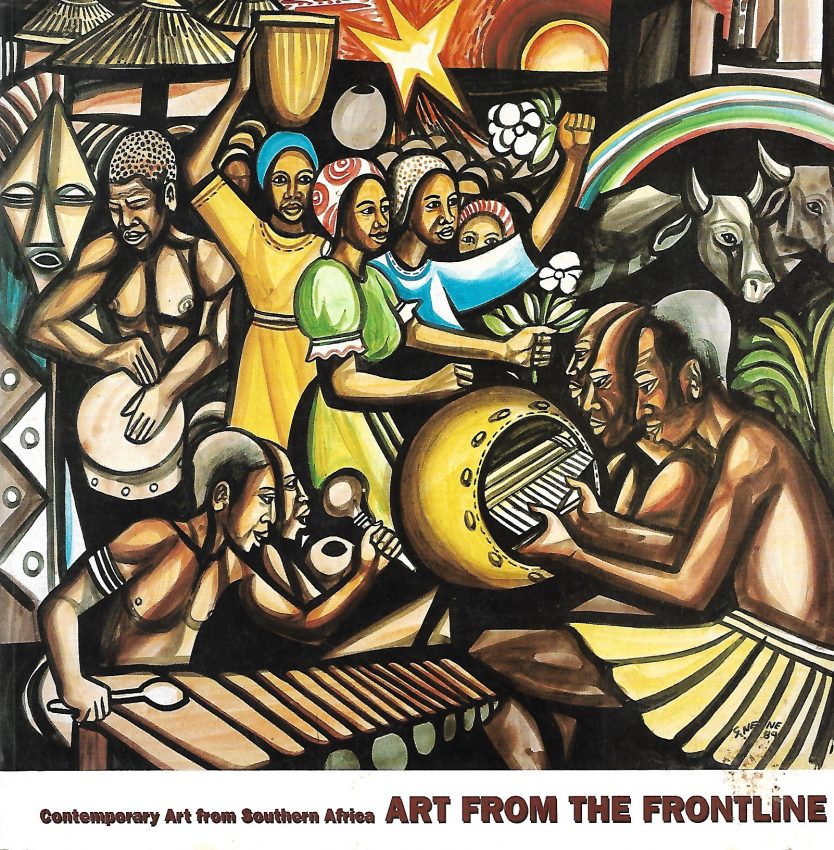

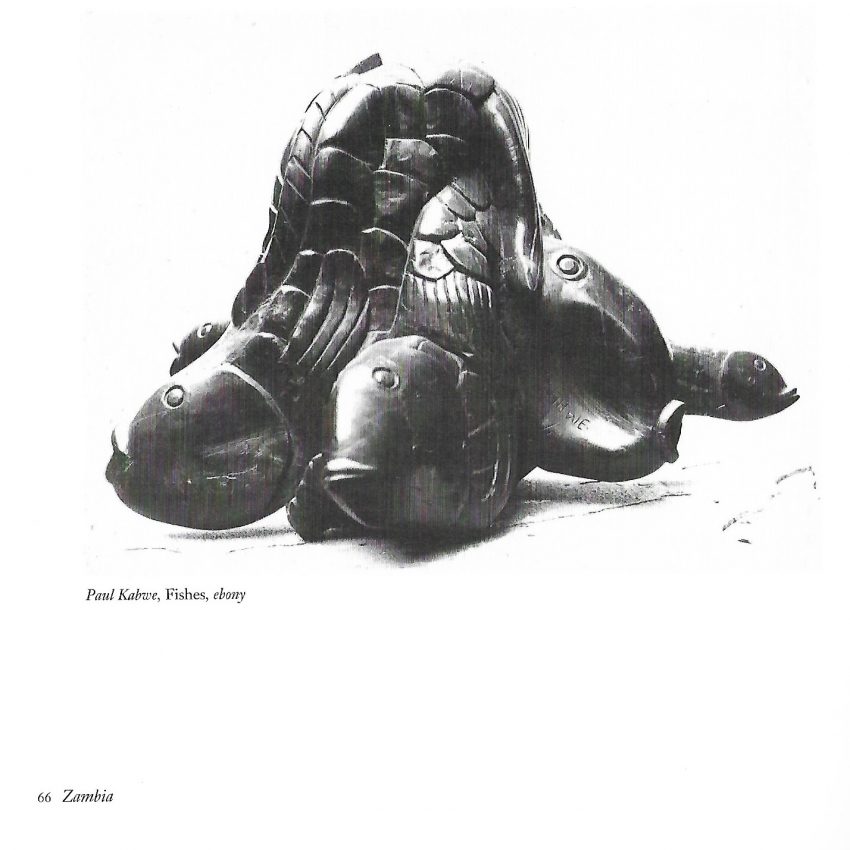

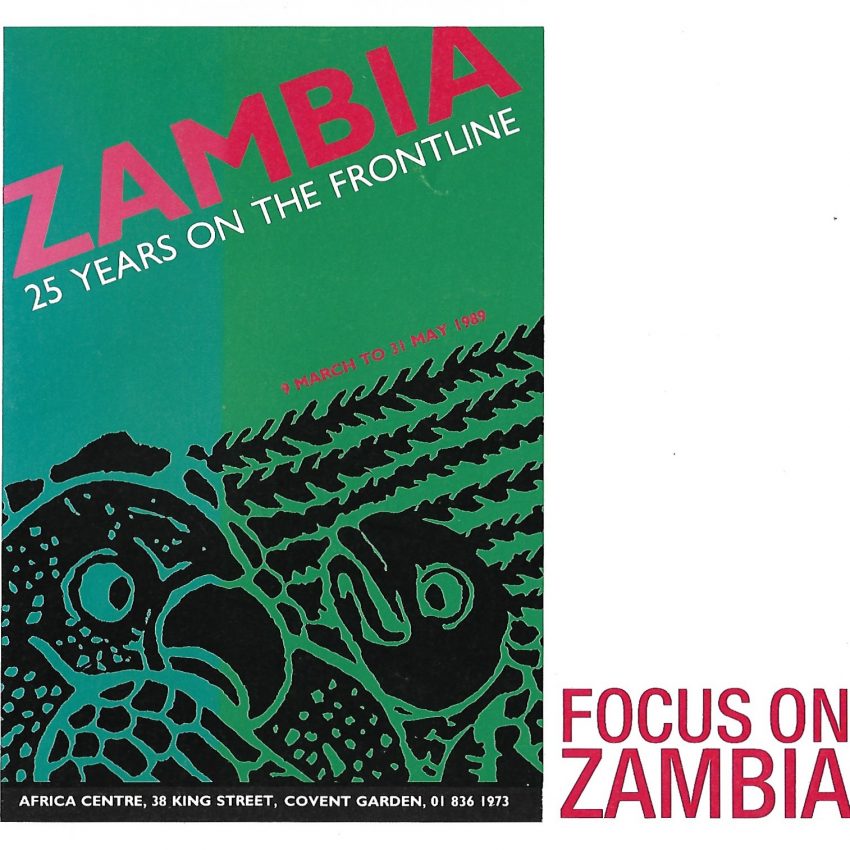

Co-operation between black artists and those white artists, many of whom were women and privileged, occurred in Zimbabwe and even in apartheid South Africa where artists often made anti-apartheid art. From 1964 to 1994 the Cold War and the wars of liberation had a devastating effect on the region and on Zambia and the development of its art. Zambian artists were cut off from their natural allies and contemporaries until Zimbabwe was free. Zimbabwe had always been better resourced than Zambia with a National Gallery and museums originally designed to serve the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. From 1978 Mpapa Gallery played a very important role as a resource and support for Zambian artists. After 1980 Zimbabwe’s artists received international support while Zambia struggled on alone. Not to acknowledge Mpapa Gallery is a disservice to excellent Zambian artists like Paul Kabwe. Kabwe, who is almost completely forgotten, appears in the ‘Art from the Frontline’ catalogue but not in the Visual Arts Council’s ‘Art In Zambia‘. In the video clip I’ve linked in here you will see Peter Sinclair who I networked with and also Tubayi Dube’s rhino sculpture sent by Mpapa Gallery to Glasgow.

Making art in Zambia between 1980 and 1994

There was no money or resources from government for any cultural projects, so all art initiatives had to be the work of private individuals. Gwenda Chongwe started an excellent craft shop which grew into the Zintu Foundation and which collected crafts of historic importance. Chongwe, a Zambian feminist, encouraged women into crafts such as weaving and batik dyeing of fabric. From 1984 Mpapa Gallery’s greatest success was in raising the profile of Zambian artists across the region and in Britain through national and international exhibitions, regional and local artists workshops until finally it helped facilitate the Mbile Workshops of 1993 and 1994. In 1991 Mpapa Gallery began to make plans to encourage more women into the visual arts. Before that the Gallery had made it possible for over 50 Zambian artists to make a living income from their work. This is an immense achievement during a time of raging inflation and of political instability resulting from the Cold War. These artists were not selling “commercial” art, but art of an increasingly high standard.

A lost Zambian Art History 1964 – 1994

In 1991 Zambia went through an enormous political upheaval. As it recovered, dynamic young artists from the Visual Art Council led by William Miko and Martin Phiri began a new period of art development. There was no written record of Zambian political history then and none of Zambia’s art history up to that point, so there was no recognition of what had been achieved previously. Henry Tayali was deservedly honoured by VAC but Henry had always worked with Mpapa Gallery and would have pointed out what was owed to it. The loss of this history and the brief and inaccurate accounts of it so far need to be put right, out of respect for all the Zambian artists and art facilitators who during an extremely difficult time were the forerunners of the Zambian art of today. In Zambia, there are now interesting women artists like Agnes Buya Yombwe and Mulenga Mulenga. There is the 37B Gallery run by Clare Chan. Cynthia Zukas of the Lechwe Gallery and the Lechwe Trust continues to work for Zambian artists every day of her life and she says that the Lechwe Gallery collection shows how deeply indebted it is to the work of Mpapa Gallery. One day there will be an accurate and well-researched art history of Zambia that acknowledges the importance of the input from women to Zambian art during those early and dangerous years. May it be soon!

8 Comments on “Zambian Art 1964 -1994 – a lost history”

You mention a video clip link. Where is it?

I miss S.Simukanga

Hi Arnold, I would be interested to hear how you knew Shadreck and if you have any of his drawings or paintings?

I know there are always people in Zambia who like to hear about the history of artists like Shadreck. Did you or do you live in Zambia? and do you know his work can be seen at the Lechwe Gallery in Lusaka?

I’ve just found one of Paulina Mubanga’s pieces so it’s great to see her remembered here

Hi Naomi

How lovely that you picked up on this post and that you have some of Paulina’s pieces! I am so proud of those that I have and they are very precious to me.

Did you live in Zambia for a while and have you any of Bente Lorenz’s booklets on pottery and some of the traditional practices around them? Would love to see a photo of what you have.

Best wishes

Ruth

Hello,

My name is Muriel Mwamba. I would like to use Art From The Frontline – A Mayfest Project facilitated by Mpapa Gallery as background cover for a CD cover. Whom do I need to contact for permission? Who was the Artist?

My contact is murielmwamba@gmail.com

Thank you.

Pingback: Apartheid within Zambian Art |

I have just found this site by chance and thought you might like to know that Paul Kabwe’s ebony sculpture “Fishes” is safe and well, having been purchased by my wife some years ago as a birthday present for me!