A writer reflects on her love of satire, and of Douglas Adams’s ‘A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’

‘There is a theory which states that if ever anyone discovers exactly what the Universe is for and why it is here, it will instantly disappear and be replaced by something even more bizarre and inexplicable. There is another theory which states that this has already happened.’

‘There is a theory which states that if ever anyone discovers exactly what the Universe is for and why it is here, it will instantly disappear and be replaced by something even more bizarre and inexplicable. There is another theory which states that this has already happened.’

‘What? But, that is NOT a satire.’

We are having pre-Christmas dinner drinks and my older sister is glaring at me from the couch. Her glare has been known to melt galvanised rubber. Conversation stutters to a halt as all eyes turn to watch me burn. The glare is because I mentioned a recent commission to write an article about my favourite satire and have decided to pick The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series. My sister has an informed view on this. Her view is that I am wrong. Under my sister’s glare, steam starts to rise from my once chilled glass of Prosecco. Her son, who is the political editor for a well-known magazine and is forced to trawl the corridors of power daily to mingle with the Westminster elite, sighs and reminds her about the Vogons.

My sister blinks, pauses. Sits back from her tiger’s crouch. We all relax somewhat and I blow on my now hot drink.

‘Well…’ she concedes. ‘I still say it isn’t satire. It’s parody.’

‘Vogons: They are one of the most unpleasant races in the Galaxy. Not actually evil, but bad-tempered, bureaucratic, officious and callous. They wouldn’t even lift a finger to save their own grandmothers from the Ravenous Bugblatter Beast of Traal without orders – signed in triplicate, sent in, sent back, queried, lost, found, subjected to public inquiry, lost again, and finally buried in soft peat for three months and recycled as firelighter.’

And aye there is the rub. What makes satire ‘satire’ after all, and did Douglas Adams write it? Surely he was sending up religion, science, politics, bureaucracy, climate change, greed, paranoia and petunias? But is ‘sending up’ the same as satire, and who judges these things anyway?

In Megan Le Boeuf’s analysis The Power of Ridicule: An Analysis of Satire

(2007), she defined satire as any piece ‘be it literary, artistic, spoken or otherwise presented’ which includes criticism, irony and implicitness. As she writes: ‘Satire is not an overt statement and it does not come to an explicit verdict, but rather the critiqued behaviour deconstructs itself within the satirical work by being obviously absurd, most often because it is exaggerated or taken out of its normal context.’

I tried to put that in my own words but she does it so much better. She also points to the fact that satire is a very useful tool for voicing criticism in ‘unstable’ – and I would add unsafe – times. Had Chaucer, back at the tail end of the fourteenth century, been publicly vocal about corruption in the Catholic Church, he might well have been labelled a heretic and a heathen, been excluded, discredited and perhaps disembowelled. Instead he wrote The Canterbury Tales. Contemporary novelists, including Adams, Fay Weldon, Martin Amis, Will Self, Bernardine Evaristo, Terry Pratchett, Chuck Palanhuik… the list goes on, have all applied the sharp bite of the pen before the sword.

I tried to put that in my own words but she does it so much better. She also points to the fact that satire is a very useful tool for voicing criticism in ‘unstable’ – and I would add unsafe – times. Had Chaucer, back at the tail end of the fourteenth century, been publicly vocal about corruption in the Catholic Church, he might well have been labelled a heretic and a heathen, been excluded, discredited and perhaps disembowelled. Instead he wrote The Canterbury Tales. Contemporary novelists, including Adams, Fay Weldon, Martin Amis, Will Self, Bernardine Evaristo, Terry Pratchett, Chuck Palanhuik… the list goes on, have all applied the sharp bite of the pen before the sword.

So why would I choose Hitchhiker’s Guide

over Catch-22 or Animal Farm, especially given the difficulty of defining satiric boundaries in the first place?

Well… I was asked for my favourite. So there.

‘You know,’ said Arthur, ‘it’s at times like this, when I’m trapped in a Vogon airlock with a man from Betelgeuse, and about to die of asphyxiation in deep space that I really wish I’d listened to what my mother told me when I was young.’

‘Why, what did she tell you?’

‘I don’t know, I didn’t listen.’

I think it holds a key place in my heart because I encountered the books in my early teens just as I headed off into a very dark part of my life at boarding school (I suffered horribly from anxiety, homesickness and double maths). There was something so compelling, ridiculous and charmingly enchanting about the first series that I still get a feeling of calm and suppressed giggles when I see the original covers. They made a very depressed teenager laugh out loud, sometimes in double maths. Although they don’t have the vitriol of the more obvious contemporary satires, there is a kind of melancholy cognisance about the facts that adulthood is a farce, the universe completely and happily inexplicable and fools and chancers are a good craic and may, bizarrely, have the escape plans by mistake. Teenagers need to know this stuff.

The conceit of authority needs pricking early, not just for when you are looking up but when you later are looking down.

‘There is an art, it says, or rather, a knack to flying. The knack lies in learning how to throw yourself at the ground and miss.’

The comedian Frankie Boyle, in his eye-wateringly acidic review of Hitchhiker’s Guide in 2018, bemoaned thus: ‘The plight of the satirist, such as it is, is a compulsion to look at the grimmest, most important thing they can think of, and then for reasons that probably wouldn’t survive a really good therapist, try to make it funny. To try to address the iniquities of their society, the satirist must manufacture some hope that what they’re doing might make a difference, then type it all up and send it off somewhere before they remember that it never does…’

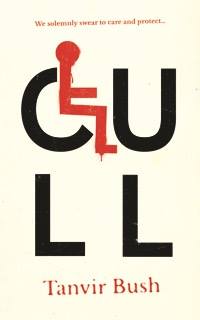

Personally, as the writer grappling with political issues of the day, satire seemed a sensible way forward for my novel, Cull, which was to be about state sponsored euthanasia, not the jolliest subject at the best of times. Being passionate about the issue, especially from a disabled person’s perspective – you may not have noticed this, what with all the Brexit braying, but the government’s treatment of disabled people was described by the UN in 2017 and 2018 as a ‘human catastrophe’ – and that was the diplomatic version.

Personally, as the writer grappling with political issues of the day, satire seemed a sensible way forward for my novel, Cull, which was to be about state sponsored euthanasia, not the jolliest subject at the best of times. Being passionate about the issue, especially from a disabled person’s perspective – you may not have noticed this, what with all the Brexit braying, but the government’s treatment of disabled people was described by the UN in 2017 and 2018 as a ‘human catastrophe’ – and that was the diplomatic version.

Most of us disabled folk have noticed this.

Hate crime and suicide is up exponentially in the last ten years and sanctions, callous benefit mismanagement and what looks suspiciously like deliberate, dehumanising cruelty has affected every single disabled person I know, and thousands I don’t. I don’t know every crip. It’s not a club you know.

The more dystopian satires felt occasionally bullish, almost thuggish in their takedowns.

They could be chilling to the reader, frightening… I explored the possibility of utilising a more sardonic style similar to Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 or even Spike Milligan’s Adolf Hitler: My Part In His Downfall. I wanted to encourage an empathic connection with the reader. Could I achieve a ‘satire’ that would encourage compassion, even an attitude change? Yet always I carried Hitchhiker’s Guide in my head and I think that helped me aim for a style that eventually allowed me to target what I saw as cruelty and hypocrisy without alienating my readers – and weaving it into a novel was a much more playful and cathartic process than chaining myself to the railings of the Houses of Parliament.

‘For instance, on the planet Earth, man had always assumed that he was more intelligent than dolphins because he had achieved so much – the wheel, New York, wars and so on – whilst all the dolphins had ever done was muck about in the water having a good time. But conversely, the dolphins had always believed that they were far more intelligent than man – for precisely the same reasons.’

Hitchhiker’s Guide is full of irony and implicitness and, although on first regard seems somewhat uncritical, I would argue that on closer examination is indeed highly and effectively critical but in the way a Pan-Galactic Gargle Blaster is critical of your brain function or The Infinite Improbability Drive is critical of physics, i.e. in a nice way.

Tanvir Bush’s book, CULL, is published this month (Unbound)

This article is from Boundless Magazine

5 Comments on “The Infinite Improbability of Satire – Tanvir Bush, author of CULL & guest blogger”

Love it Tanvi I can just image the scene!

Tanvi does make scenes come alive

Frankie Boyle had a point when he said that satire does not change society, it will rarely influence an election or topple a dictator but it can do some good at an individual level. It is difficult to believe that anyone who read the bit on a space ship powered by the dickering over a restaurant bill would ever spend time arguing that they did not have the sweet. I also wonder if anyone at the Home Office or the DES ever read the HHG if they had surely at some point their conscience would whisper ‘I am being a Vogon’. For me the greatest contribution of satire is the realisation that someone out there is paying attention to what is happening and has realised that at the very least they can cheer us up and let us know that we are not alone.

Yes indeed! HHG did brighten up our lives enormously! I hope that you’ll also be able to love and enjoy Tanvir’s CULL.

I’m sure I will, haven’t got round to it yet so much to read so little time.