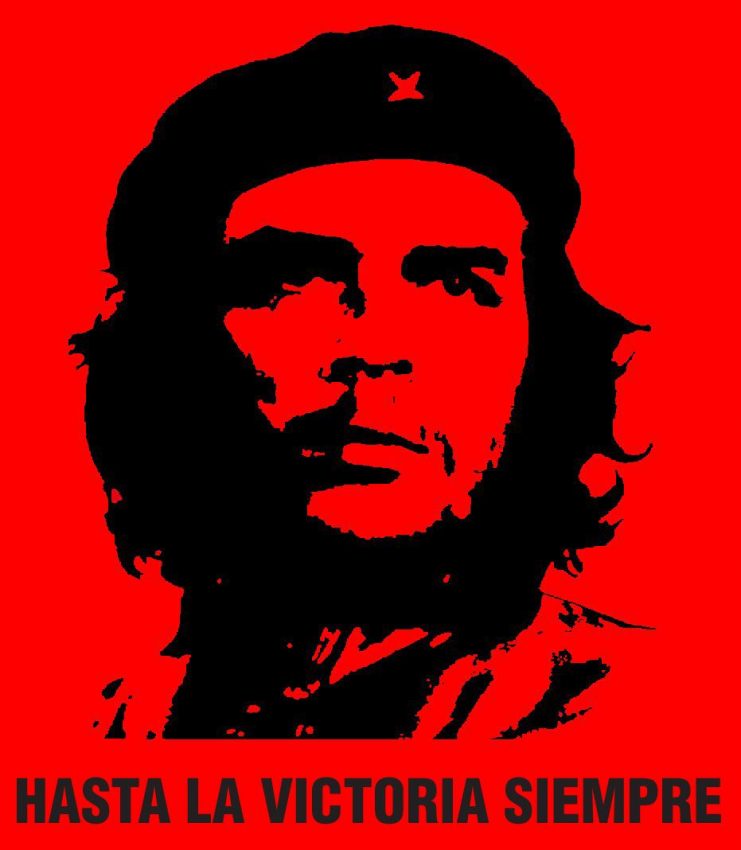

Che Guevara and that famous poster

Old revolutionaries will remember the importance of Cuban screen prints as propaganda tools for the fight for freedom all around the world. In 1968, my communist friend, Bill, insisted that we visit the Cuban Embassy in London to see this particular brilliant and sophisticated form of art and agitprop. We all remember the poster of Che Guevara. Those were the days of international socialism, demonstrations against the Vietnam war and the London and Paris student uprisings when posters like this one decorated our streets. The Cuban Embassy was open and welcoming. They understood the power of excellent art and cinema. Then and there, I planned to visit Cuba. Soon after by contrast, the nearby Chinese Embassy, in a paranoid frenzy, threatened to use axes against the British press. The1968 Chinese Cultural Revolution under Mao Zedong had just begun. It was to end art, music, culture and creative thought in China for decades.

A magic journey and an enormous culture shock

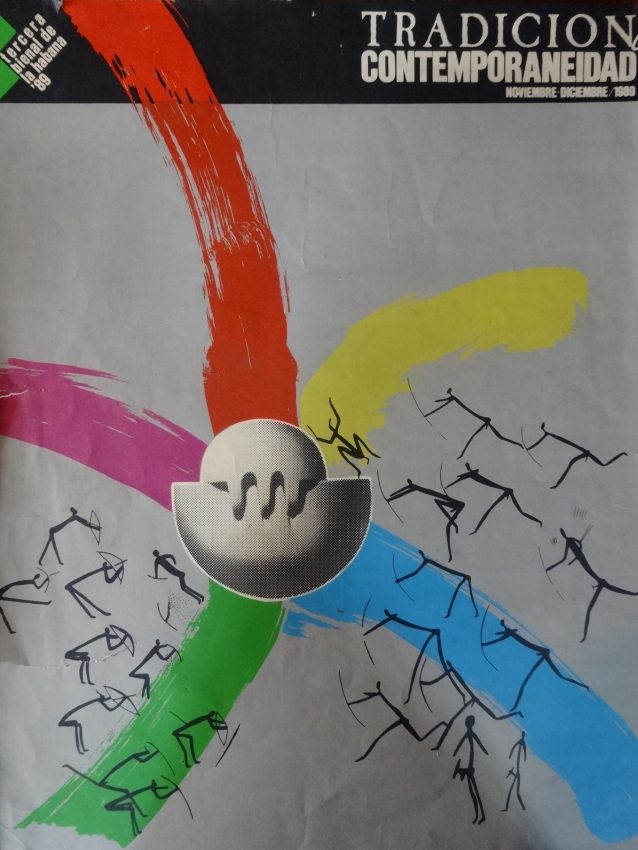

On the 29th October 1989, at the invitation of the Cuban Embassy, I flew from Zambia to the Tercera Bienal de la Habana – the Third Havana Biennial – to talk about Stephen Kappata, the Zambian artist whose art was on show there. The Biennial theme was Tradition and Contemporaneity in the Third World. My flight from Lusaka was generously paid for by the Lechwe Trust. I was routed via London and Madrid but my booking was lost and I ended up travelling from Madrid to Ireland, then Newfoundland and finally to Havana. On the flight, I read a novel, Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel Garcia Marques which intensified my sense of unreality. This trip would challenge me and question my perceptions, presumptions and knowledge of other cultures. I knew contemporary Zambian art did not draw on its traditional roots for inspiration and was uninformed about recent international art movements. I knew that the Zambian art struggled to survive in a difficult environment. Together with my partners, Joan Pilcher, Cynthia Zukas and Patrick Mweemba at Mpapa Gallery, we worked to provide resources and encouragement to Zambian artists. It was my intention to carry back to the artists the new concepts and experiences I would encounter.

A spell-bound island at the end of the Cold War

Cuba was desperately poor. Cubans could have free medical and dental treatment, but clothing and food were scarce. Many Cubans attended the Biennial events to eat fruit and drink the rum as well as look at the fantastic art. As guests, we ate well enough, but food ran out in the hotels if you didn’t get early to meals. Ernest Hemingway’s famous cafe didn’t have rice and beans. Drinks in bars cost dollars. The fire escapes at my skyscraper hotel were locked against hungry locals or those dying for whisky. Life in Frontline Zambia, also under boycott, had given me sympathy for such problems. The day before the main opening the walls in the art gallery were still being constructed because of delays in funding. With a degree of ironic fellow feeling, I observed that even in the national gallery works were displayed in the same cheap clip frames we used at Mpapa Gallery. For the first time, I saw people wearing bum bags (American: fanny bags) to safeguard themselves against petty thieving. ( I started to use one on my return to Lusaka.) Everyone connected with the Biennial worked extremely hard but some of the women complained of a macho society. Men fathered children but wouldn’t share childcare time, even though Cubans didn’t have many children. I was invited to visit an Afro-Cuban community and heard complaints of discrimination in both arts and in society. The noise of traffic and unsilenced vehicles without upholstery in a very hot Havana was unbearable, especially coupled with the foul smell of imported Russian fuel. I witnessed a near riot over infrequent bus services.

Exciting and extraordinary art and artists everywhere in Havana

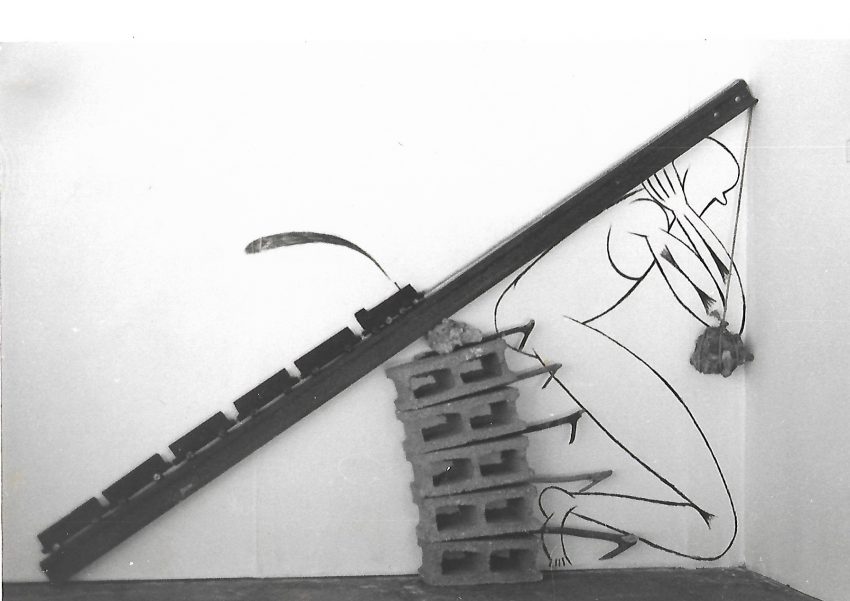

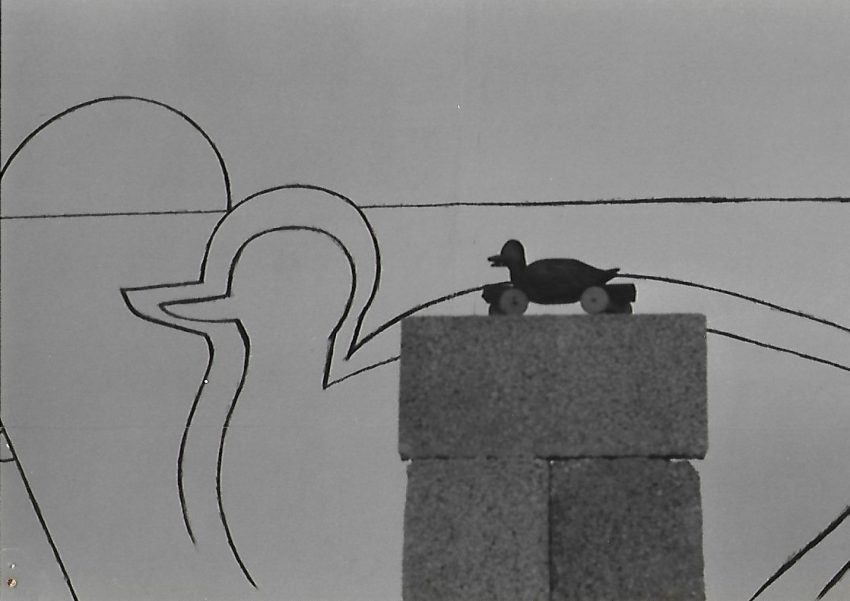

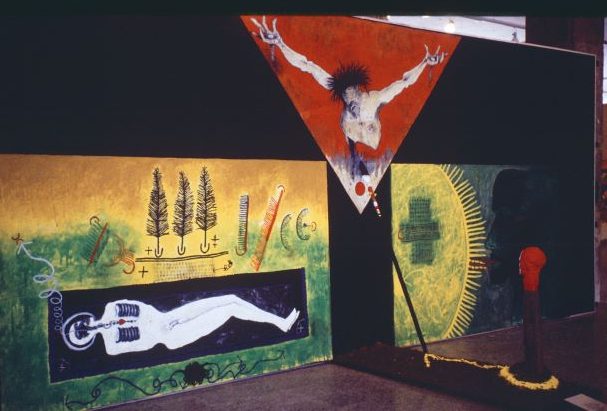

The art was amazing – stunning and inspiring. Cuban artists were angry and confrontational with regard to Cuba’s politics and state control. I was impressed by the enormous courage, vitality, variety and creativity on display from every country in the Third World. There is much more to tell about the Biennial than there is space and time for here, so I’ll stick to the connections with Africa as written in my report and notes at the time. Cuba’s connections with Africa were immediate and direct. Soldiers had recently returned from fighting in Angola and winning battles against the South African apartheid army. (The Museum of the Revolution taught me more about that war than anything I had read at home.) José Bedia made a wonderful installation in the Castle on this mix of war, African religion and Cuba that needs a whole post dedicated to it. Slaves had been brought to Cuba from the borders of Zambia, from DRC (Zaire) and Angola and their cultures are embedded in Cuban culture and in its Syncretic religion. Manuel Mendive, a revolutionary Cuban artist who had previously exhibited at Mpapa Gallery, made a strange and beautiful ceremonial performance and installation using dancers and painted bread which married Cuban and African beliefs. I will never forget it. Much of the Biennial was in the form of art installations and I felt strongly that this was a natural way for Zambian artists to go and I, myself, would increasingly exhibit my art as installations.

Talking openly about colonialism and art in the Third World.

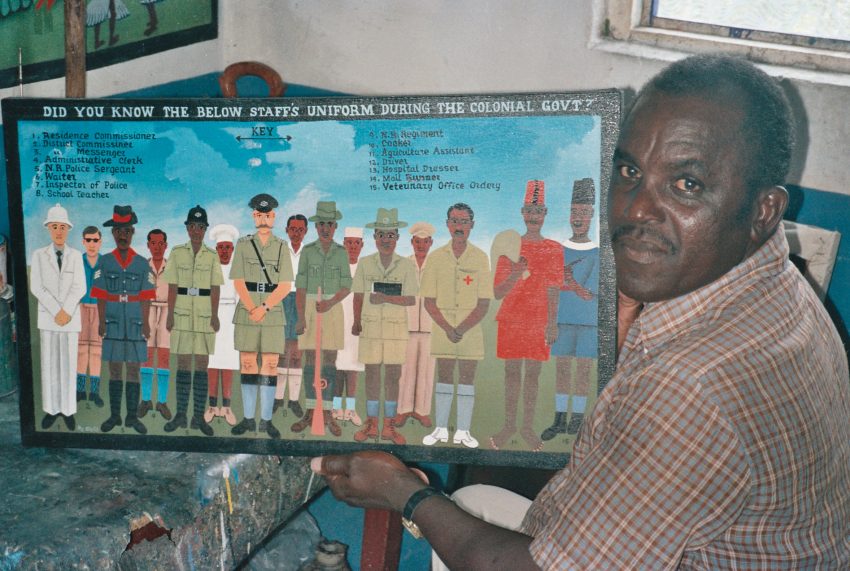

Rashid Diab, a Sudanese artist, and Badi-Banga Ne Mwime, a Zairean art critic. travelled to Cuba on the same plane as me. They both spoke in the Open Forum at the Biennal. Badi-Banga Ne Mwime spoke of art schools in Zaire and Zairois narrative comic strip art which bears some similarity to the art of Stephen Kappata. Rashid Diab rejected the idea of ‘a third world in art’. He talked of the marginalisation of African art and also insisted that art must never become a political tool, or be sanitised and de-spiritualised for a ‘white market’. For me personally, the talk by an art critic from India, Geeta Kapur, was the most significant. She said that questions of identity for artists from the Third World trap them in inequality, make them captives of capitalism and of the First World art market. Traditional heritage is not disinterested but can be reactionary, not progressive. Henry Tayali, who had attended the Second Havana Biennial as an invited artist, believed these issues were central for Zambian artists. The difference between Tayali’s and Kappata’s art is an indication of the wide richness of Zambian art and of the Cuban view of Third World culture evidenced in the Biennial. Mpapa Gallery had the same broad approach in its engagement and support of Zambian artists.

My talk about Zambian artists and Mpapa Gallery,

The moment came for me to speak in the Free Debate at the Biennal. There was no money left to pay a translator but a gentleman in the audience generously offered to translate as I spoke and I was able to have a friendly and fascinating discussion around the 50 slides of Zambian art I showed. I had also brought examples of prints, crafts and photos with me. The audience was mostly students and Afro-Cubans who wanted to hear from someone from Zambia. They enjoyed Kappata’s paintings but asked me why the spirits of their African ancestors were not evident in Zambian art. I explained that in Zambia, tradition IS experienced as contemporary but the lack of resources, materials, education and government support for art and culture in Zambia and the pressure of being a Frontline State in the war against apartheid during the cold war, had trapped Zambian artists in a tourist market. Mpapa Gallery was determined to help artists break out of this dependence and find their own forms of expression not dictated by a ‘Western’ art market, neo-colonial attitudes and representational forms of art. Rereading the speech I made in Cuba and my report on the Biennal confirms once again, the important and progressive role of Mpapa Gallery and Joan, Patrick, Cynthia and myself, in the years between 1987 and 1995.