Art and storytelling 200 years later by a distant descendant.

Born into the British Empire during the Second World War in a colonial country that no longer exists, I’ve been flung around in a turbulent vortex of political and personal change. My art and my writing are the ways I hang on to the world spinning around me. I have no answers, just more questions – I fly around a disintegrating centre – illustrating what I don’t know or understand by writing and making art. I’ve just published my seventh book – When We Were Wicked – two short memoirs and ten short and shorter stories about saints and sinners in a wicked world. It follows my memoir When I Was Bad which tells of how I tried to be good in a colonial world and was bad in an apartheid regime.

Making use of war veterans OR how my family came to be South African

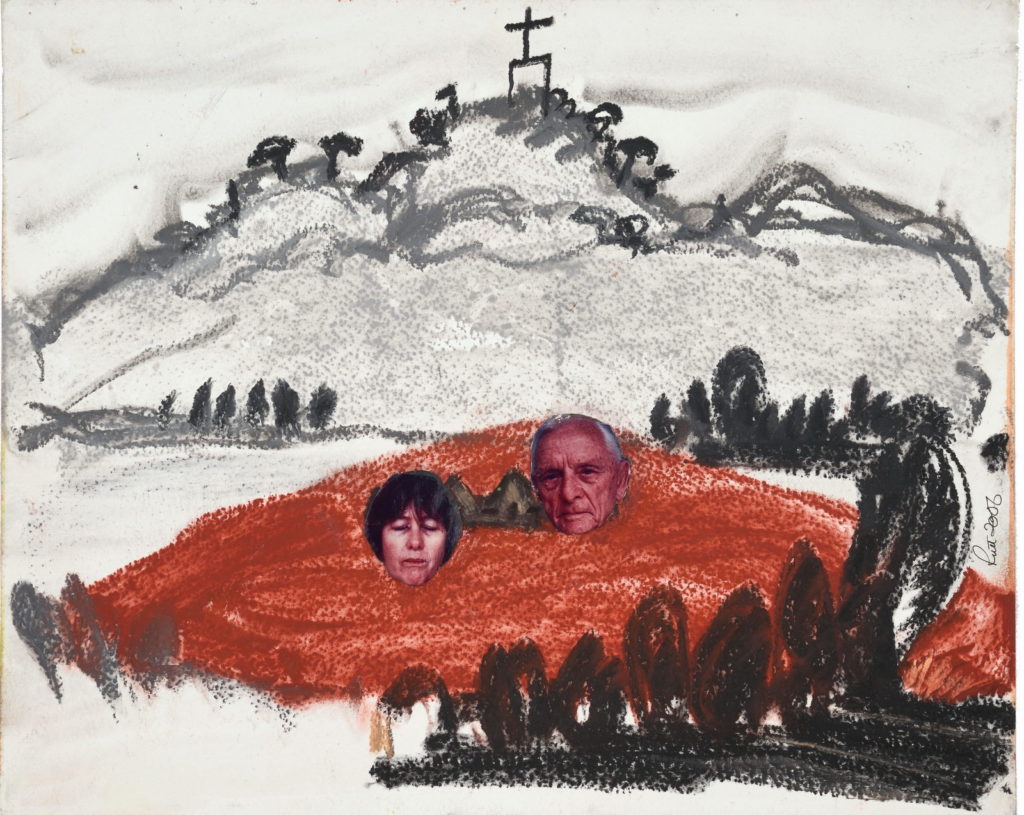

Encouraged by the British Government as a way to escape the poverty and unemployment after the Napoleonic wars, my maternal forebears, the Nelsons, came to the Cape Colony, later British Kaffraria, in South Africa in the 1820s. Settlers were promised fertile farms in an uninhabited land, but the region suffered drought and amaXhosa pastoralists already lived on it. The British governor needed English immigrants as a counter to the 1652 Dutch settler population and as a barrier against Zulu expansion southwards. Many years later, the 1820 settlers reckoned themselves to be a South African English elite and my great-grandmother Nelson was proud of her connection to Admiral Nelson’s first cousin. Nelson had begun his career as a 12-year-old cabin boy but, with help from a relation, he rose to be the Admiral of the Fleet and to commit war crimes, as well as save the British fleet. Are the colonists’ stories the same as Nelson’s – rags to riches or just stories of survival? Some colonial settlers become wealthy. A few, like C J Rhodes and Alfred Beit, became rich and powerful after making fortunes in diamonds or gold and many settlers did benefit from their risky post-war migrations. Some made money and some acquired status and power, at least for a time. They did so by crushing the African pastoralists and warrior tribes and exploiting them as an underpaid disenfranchised labour force. That could not last. In an art installation in Bedford in 2006 entitled The ‘true’ History of my Past I made drawings exploring the history I saw through the eyes of a child.

Sleeping with the enemy in my family

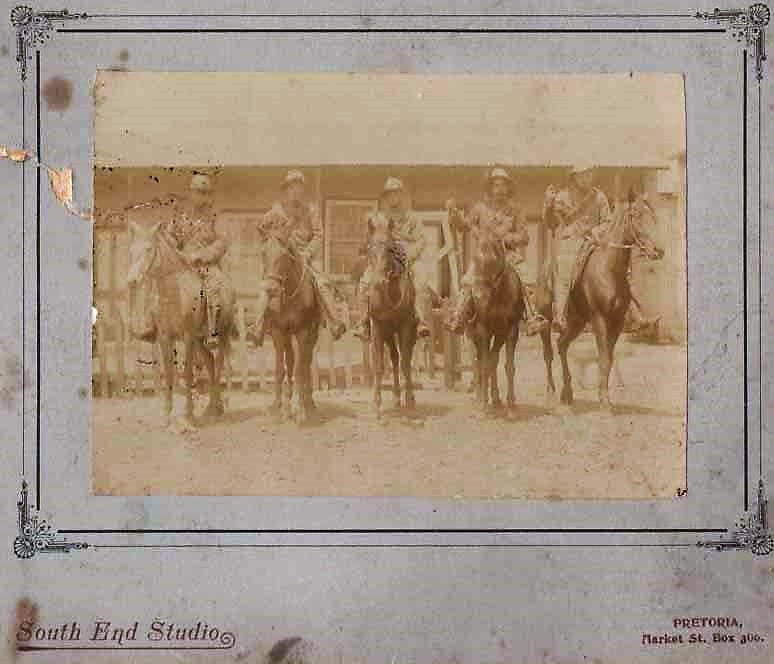

My maternal grandmother’s German family, the Meinekes, came to South Africa after the 1840s. They may have been mercenaries who fought with the British in the Crimean War and then fought with them against the amaXhosa, a few finally going on to help the British suppress the Indian Mutiny. My ancestors, however, were probably dispossessed German peasants of whom little is known except that they were poor. My grandmother left school early and went barefoot as a child. I have a friend whose Afrikaans grandmother died in a British concentration camp. She thought the Meinekes’ natural affiliation as German peasants would have been with the Boers – the Afrikaner community. My paternal great-uncles fought with the Imperial Yeomanry in the Second Anglo-Boer War against the Boers. One was an alcoholic. One changed his name and is buried in an unmarked grave. Both vanished from family history. Does this mean my family was at war with itself even then? A substantial part of my DNA is Germanic – my father must have been on the opposite side to his wife’s relatives in the Second World War. As ‘Hamera and Hartley‘ my friend Krystyna and I put on an exhibition in 2008 at New Hall, Cambridge called ‘Finding Fathers‘ in which we explored the complexity of our relationships with fathers, one who survived a slave labour camp while the other fought in the Second World War.

Loading the mother lode

My maternal grandfather, Ben Burton, was a poverty-stricken alcoholic tailor, so perhaps marrying him was not the smartest move for my Germanic grandmother. He inherited his tailoring business from his grandfather, a military tailor in the British Army during the Xhosa Wars until that trade declined. I visited my mother’s childhood home in the 1980s and I was shocked. Their wretched home was half the size of the two-up, two-down slum dwellings I saw in the Falls Road in Belfast in 1969. My mother’s male cousins became doctors, academics and judges, but she couldn’t afford to take up her scholarship at university and travelled to find work as a clerk at the age of 16 in Rhodesia during the Depression. There my mother stayed and there I was born. My family history wasn’t known to me as a child and my grandmother never spoke of hers, but like all white children, I was taught to honour the Great British Empire at school.

Parental depression

My paternal grandfather, (Senor) Alfred(o) Ernest(o) Hartley, came from a Bradford carpenter’s family. His father, William, made money from shiploads of guano until all three of his ships sank. Alfred married into a well-bred London family and worked as a wool trader in the Argentine. In 1922, after the First World War, he bought land in Rhodesia intending to farm dairy and tobacco, a day’s ox-wagon walk from the main town. The farm business failed when the Great Depression hit in 1929 and he returned to work in Buenos Aires. My father was left at 19 going from one temporary seasonal overseer job to another on isolated rail sidings and farms. The Depression ended, my parents married and the Second World War began. My father Stephen, went off to fight in Abyssinia and Kenya and my mother struggled to survive with a baby and a toddler on his often-late soldier’s pay in a remote Nyanga bush village. Made paranoid and obsessive by deafness and the Depression, all my father cared about on his return from war was reclaiming his father’s land. “Enough land for maize and chickens,” he said. “Enough land to survive on.” The tiny acreage that remains is where my sister farms today.

Sending sons to war to buy land

My stepfather’s parents came to Rhodesia to farm at the same time as my grandfather. His widowed mother could not make the farm pay, so at 15 years old he was sold into an RAF apprenticeship and then swept off to the war in the Far East. He returned to find his family farm sold, but while British ex-airmen and soldiers were once again offered cheap land in colonial Rhodesia, he did not qualify and had to start from scratch as a farm assistant until he saved enough to buy his own farm. War played such a significant part in my family history and in colonialism that I decided to explore it in my next two books. The Shaping of Water and The Tin Heart Gold Mine

Good, bad and ugly colonists – and the colonised

What were colonists searching for? Adventures, knowledge, riches, anonymity? Family homes? Places of safety for their children? Somewhere to redefine themselves in new ways by reclaiming old ways – by building medieval castles or thatched Tudor cottages decorated with horse brasses, family trees and dubious coats of arms in Africa? Somewhere to be rooted in the past and the future? After 1807 ways to end slavery? Ways to educate and to Christianise and to provide better health for the “indigenous”? Ways to make a better world? Ways to justify their existence? Power and domination. Riches. solutions to their never-ending wars and increasing population. Freedom and equality – I guess this is what immigrants hope for too.

What am I searching for?

Ways to understand the history and the problems that I’ve inherited. To see what I need to address and redress. I’ve used my art and my writing as ways to explore who I am. what I am and what I want to be today and tomorrow in the brief time left to me.

I’m writing my next book – its working title is – How Not 2B(^) In Africa

I am African and there is no escaping my colonial past and the racism that is inherent in it and it is here that I will ground my next novel – it may be about the evils of coercive control and abuse and how we fight to escape them – and whether or not some of us may succeed …

11 Comments on “Blame it on the man in the brandy barrel – Admiral Nelson”

This is fascinating, and I find myself on a similar journey of trying to understand my family’s colonial history with all its warts and inter-generational trauma and complexities and nuances. I hope to write a book about it one day too.

Hi Andrew – I’m so glad you found my post interesting. I think that all of us – the individuals involved in this shared history can begin a voyage of discovery and understanding by sharing experiences and by writing about it too. I think this kind of history is so valuable for its human touch rather than the stories of battles and powerful people. Hope to read your book one day – best wishes Ruth

Tears. Not the way I see it but I feel your pain. Granny B used to say the Meinekes were “gentleman farners”. I only met my grandfather Ben Burton once, in a hospital bed in East London (eastern Cape Province). I had just turned six. My mother had made herself and me and my little sister Hilary matching dresses in fine red and white stripes. As we approached his bed, my grandfather covered his face with his hands and exclaimed, “O. O, three pink elephants!” Next, he proceeded to baffle me by proving I had eleven fingers and not ten at all… I was quite cross. Memories! But no research.

Hi Lorraine – thank you for your comment – I think its all the more interesting because we do see things differently. You and I and Charles and our siblings are now the keepers of family history and I’m absolutely fascinated to hear your story about Grandfather Ben. That would have been just after WW2 perhaps? Funnily enough, my father used to say he was a ‘gentleman farmer’ and then add with a laugh, that it meant he didn’t depend on the farm for his income which was just as well because there wasn’t any. I think it also meant he didn’t have to hoe the land himself.

My mother and her grandparents both had African trading stores – the Meineke’s sold magehu? – uMqombhoti -maize beer – I don’t know the right word? and my mother had a tailor.

Fascinating. In Malawi they drink Chibuku which comes in a blue abd white cardboard box and which looks revolting.

I’ve been told some very interesting information about Chibuku by Verona, a friend in Zambia. Green beer brewed from sorghum, millet or maize was drunk through southern Africa but a German called Heindrich decided to brew the beer in quantity more hygienically for the mineworkers on the Copperbelt. They could buy the beer on tick and have the money was deducted from their pay at the end of the month by entering it into ‘the big book’ or the ‘chi buku’ so that is how it became known as Chibuku. I’ve drunk both Chibuku and green beer – they tasted okay but weren’t exactly thirst-quenching as they were more like a thin porridge.

My memory is from 1946. 1946 was a seminal year for me. It was the year I was a flowergirl ( to my AuntyPhyllis); it was the year I saw the sea for the first time; it was the year I turned 6 and had a birthday party with a cousin called Michael Burgess whom I have never seen or heard of since. I also think it was the year I heard, after we had returned to Southern Rhodesia, that my Grandfather (Ben) had passed away. It was also the year that I started school and the year that my sister Diana was born (in November).

I like the sound of my Uncle Steve’s sense of humour, by the way!

I do appreciate what you have told me – there is no one left to tell us what happened then so your account really matters – I’ll work out Grandfather Ben’s age – I must have been over two years then.

Blame it on the good times. Blame it on the boogie.

I read the blog , found it interesting in terms of how life and circumstances change our lives and the world. But I have an issue with your terms Bad and Wicked. It is not you that the terms should be applied to, but the situations, first of your ancestors and then your own experience of religious lack of tolerance. We have just had a few days of hearing and watching how Jews survived the Holocaust. If a young child survived in the forest by pinching food he/she was not bad or wicked.

I assume your art helped, and it is great art whatever the reason, but perhaps now you have to try writing on positive situations and how good can come out of the bad and wicked. Not easy in these times, when the corona pandemic has brought more negative results of racism (increased risk of dying in Afro-Americans, American Indians and Hispanics), attacks on Asians in the US, hoarding of vaccines and less solidarity and excuses for the so-called developed world to ignore what is happening in Yemen, Syria, Myanmar.

I don’t really know any positive outcomes of the pandemic, except that there were local support activities, working mothers on leave without pay learnt to cook with their children, and some families used the time at home to really get to know their children. Not saying it was all good – just some good things.

I think it’s time for some positive writing about how bad can lead to good and get out of the bad of the past. Like how we grew up in Zimbabwe and Zambia and turned out to be capable women that can contribute to literature, art and for me, to health of national populations. We didn’t have the so-called culture, theatre, museums of London and Paris, but many of us were inspired by good parents and others.

Look up Isaac Ochberg (Cynthia’s grandfather) for inspiration of bad to good.

Thank you Aviva for your comment and for reading my posts. I do appreciate your interest and your participation very much. I must confess that you are right – I do need to be positive and in fact – I do always try to make something good happen in my novels and to end with hopefulness but maybe I need to watch any negativity more carefully. I intend to research the interesting Isaac Ochberg soon! My choice of ‘bad’ and ‘wicked’ was partly ironic and satiric – it was also partly because I hope are marketing ploys that attract interest.Yours, Ruth