Can standards of beauty be imposed on artists?

What is beauty and is it an essential part of art? Is there such a thing as a universal standard of beauty in art? I ask because the questions are relevant to discussions about the impact of colonialism on indigenous cultures. That’s an enormous subject and there won’t be any quick or simple answers, just many diverging, coalescing and colliding viewpoints. What I believe is that the idea of beauty is not as central to art as its purpose – or to the desire that drives its making.

Ideas to consider

I’ve assembled a few ideas for consideration. The first idea is mine – here it is –

Art is the ritual rearrangement of dirt, both physical and psychic to ameliorate death.

What I mean is that art is literally made from ‘dirt’ or various material substances from rock and pigment to sound and movement. It is also made from the ‘dirt’ in our souls whether that is our sin or troubles inflicted on us that we wish to purge. Artists do also express joy. In its broadest sense art includes time-based performance, ceremonies, music and dance as well as installations and 2D works that are seen through ‘ritual’ observations that are both spiritual and physical. Art is, for me, a way of cheating death and perhaps improving, altering or understanding life and it’s done through forming materials (or words) into comprehensible shapes and events. As Hamera and Hartley, Krystyna Hamera and I put on an exhibition at a church in Cambridge dealing with dirt.

Dannie Abse, a poet, has said that ‘Death is the patron of the Arts.’

Mary Douglas, an anthropologist, wrote that ‘Art and religion are rituals necessary for social hygiene.’

I understand Douglas to mean that the way we make sense of our mortality, our messy lives and inevitable deaths is by categorising actions into sacred and profane – or if you like – clean and dirty – we must always manage both because we’re stuck with them.

The concept of abjection

Julia Kristeva, a complex feminist philosopher, writes about ‘abjection’ taking the concept of social hygiene further to explain why certain groups of people in society become the ‘abject’, are excluded and even murdered. She says ‘abjection’ disturbs identity, system, and order. Every society has at some point turned a group of people into scapegoats and victims and committed crimes against them. In too many societies, women and LGBT people still remain the ‘abject’. Defintions of ‘abject’ and ‘abjection’ include extreme states of hopelessness, victimhood, degradation and humiliation. There are obvious links here to how the colonised feel about their colonisation. Kristeva explains further linking this process to art:-

‘The various means of purifying the abject – the cathartic processes – make up the history of religions and end with that catharsis par excellence called art that is both on the far and near side of religion.’

The main purpose of art

None of the previous ideas mention beauty as the main purpose of art. What is said is that art is an essential part of our societies and our lives. I suppose that this is what I have always felt. I believe that this means that whatever tools artists find to use, whatever culture they are sourced from and whatever technology they exploit, artists will always find ways to purpose them, to shape them, and to weaponise them into new and contemporary traditions that will transcend the origins of those materials and enforced ideas. Cultures have died and disappeared in the past. Power, whether colonial, indigenous, or global will dominate for a time and eventually die. The creative spirit of all humans will find ways to survive and to make and shape meaning from death and life and endurance.

It often won’t be beautiful or even pretty but it will be art.

I’ve chosen to illustrate this post with photos from an installation made by Krystyna and myself working together as Hamera and Hartley in Cambridge. We looked at both female and male artists who used dirt, death and faeces in their art. At that time Damien Hirst was the most famous exponent using a dead shark, rotting bull’s heads and covering a human skull with diamonds.

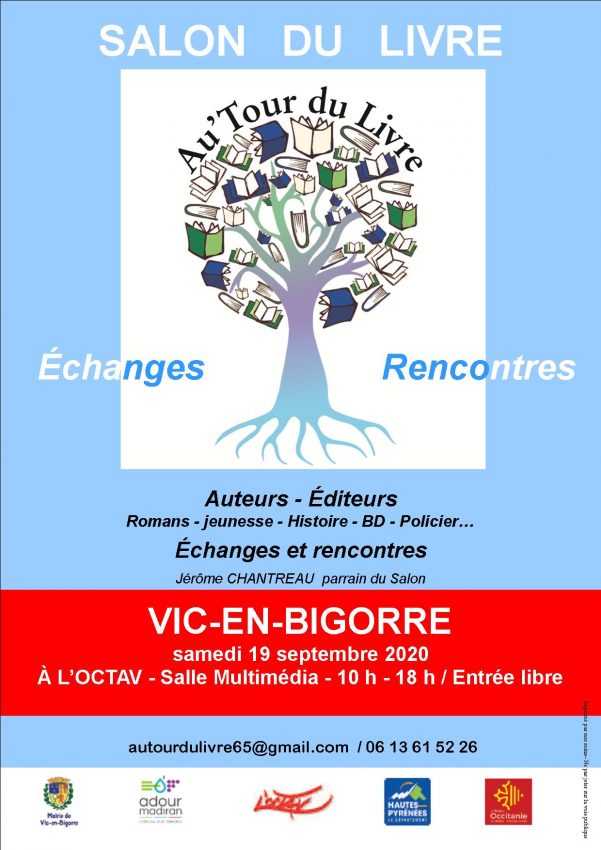

Today I’ll be taking part in Autour du Livre, the book salon in Vic en Bigorre. I’ve have also amazingly been short listed for a short story at the Charroux Festlit. Results later today.

3 Comments on “Beauty, culture, colonialism and the purpose of art”

It has been announced today that Ruth is Runner-Up in the Charroux Prize for Short Fiction 2020. Well done to her!

Congratulations Ruth – fantastic accomplishment.

Thank you Barbara -from someone like you – a compliment means a great deal