I’ve had to learn a different history

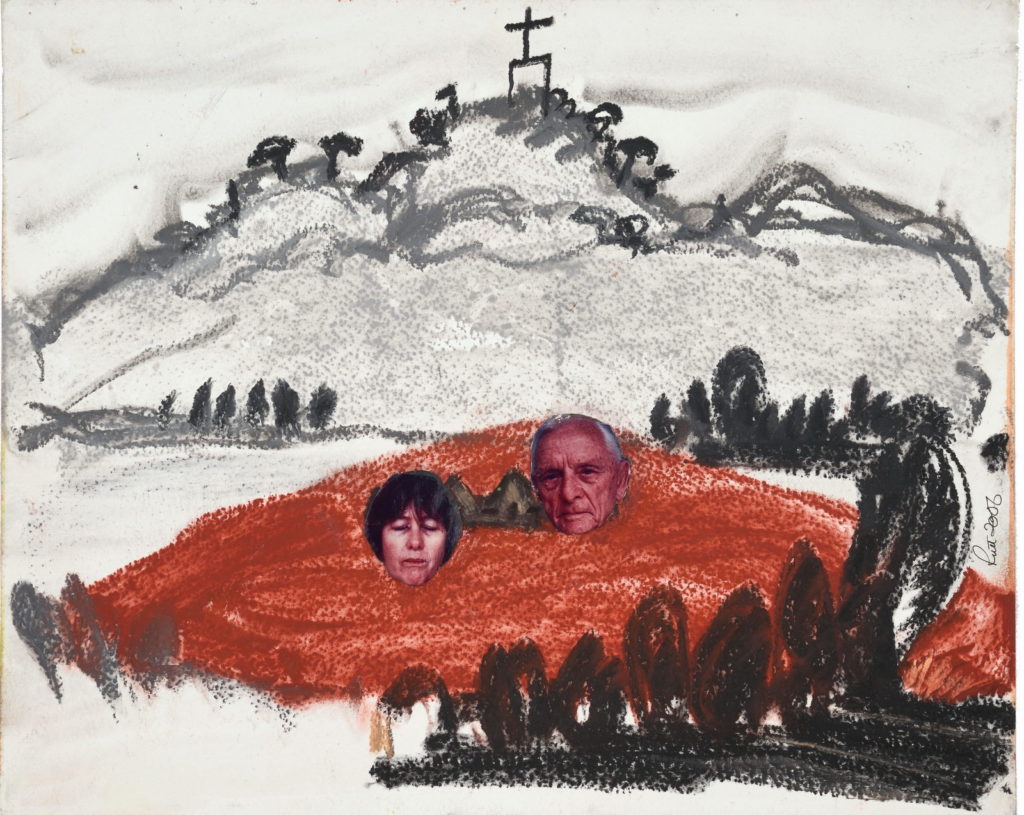

I grew up during the British Empire when Cecil John Rhodes was the hero of school history but I had a great teacher. She was a cynical idealist who toed no party lines. At Cape Town University under the Rhodes Memorial, I followed up her questioning style and explored a more radical history opposed to racism and oppression. That enabled me, in 1973, to rewrite the South Africa long-distance learning course used by my Zambian students. My personal history has been rewritten without my agreement but that is life and happens in every family. None of us sees our history or our world from exactly the same angle. History can be twisted to disadvantage or to denigrate other people so it’s a human requirement to keep on asking questions of history that take us closer to the truth. So for that reason, I’ve come to use my art and writing to interrogate my history and my experience. The drawing above, for example, is titled ironically “The “true” History of my Body”, It’s about the way my experiences feel to me and not about my real body just its mythical meaning for me.

I’m not a historian but we are all steeped in history one way and another.

The drawing I made above is of my father’s farm bought by my grandfather in 1922 and now the site of the new Zimbabwe Parliament. We constantly reinvent our own personal histories and we also have different versions of the history that shaped our countries. It’s painful to grow up in a country that you think is good and then find it guilty of crimes against other peoples or nations. Germany is not the only country to face a terrible past. Every nation has done dreadful things at some time. White Rhodesia, Zimbabwe, apartheid South Africa, Great Britain, the United States, Chile, Russia, China, Myanmar, Yemen, Uganda – the list goes on and on. Even victims aren’t always innocent of wrongdoing. The answer is that we must keep on rewriting history after impartial and thorough research to make it as accurate and as true as possible. Cecil John Rhodes is now seen as a monster who amassed a vast fortune. He did, however, leave it all to Zimbabwe and South Africa and to educational foundations. Mugabe, on the other hand, was a freedom fighter who looted and impoverished his country. The study of history certainly challenges prejudices and preconceptions

History can be lost and people do disappear

History, both as images and words, needs also to be kept safe, preserved and archived. It’s easily subject to fashion and can be discarded. It can be weaponised or disguised by politicians for dubious reasons. Ambitious individuals often claim to be the originators of innovations they stole from someone else to give themselves a better history. Russia and Poland are busy rewriting their histories. Hungary is obliterating some of its histories. Great Britain is only now, 75 years later, acknowledging the Afro-Caribbean pilots who flew in the Battle of Britain and the millions of Africans who fought for its Empire in WW2. South Africa hasn’t yet written the history of the help it received from Zambia under Dr Kenneth Kaunda during its liberation wars and most extraordinary of all, Zambia itself seems not to remember those years either. I have put in a link to a lecture about President Kaunda’s help for President Mandela given by Professor Hugh Macmillan. Who would think that such recent history can cause disagreements!

Fake news, and false histories

We are all gullible at times. There are stories we hope are true and histories we would rather have. Its sometimes difficult to question what people tell us because they are family, friends, community leaders, both religious and secular, celebrities, or perhaps they seem very well-informed and clever when they may in fact be conspiracy theorists. Fake news can have well-designed websites and amazing photo-shopped pictures. There’s plenty of misinformation about our past histories. If, like me, fake news and false histories worry and confuse you Snopes.com have a good site for investigating it

The meaning of history – legacies and legends

I suppose we all want to respect our ancestors and we would all like to have great ancestors worthy of respect. We want to be legendary heroes ourselves rather than legendary for our crimes and mistakes. The heart of history is not simply about the proven facts of past events but about the story of our endeavours as humans to make a better world and to make a better connection between the past – our past – and the future for all of us. That is why history matters and why I enjoy knowing about it. It’s also why I’ve written two of my books – The Tin Heart Gold Mine and The Shaping of Water; they are the previously untold stories about forgotten people left out of history.

5 Comments on “Writing, art and the rewriting of history”

Fantastic, honest and unadulterated.

Thank you so much Eugene – I hope to read your histories too someday!

Thanks Ruth. I’m not a historian either, but History is such an important subject for understanding not just the past but, possibly more important, the present. At the wonderful, multiracial University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in the early 1960s one of the most read books (and not just by historians, it was cult reading) was E.H.Carr’s “What is History?” It made a generation of students realise that history is malleable, showing how in successive waves of History-making different material gets rejected, reinstated, re-evaluated, discovered. What is “known” changes. (This was pre-Foucault etc)

It paved the way for the “Hidden from History” idea – moving away from the deeds of “Great Men” to look at enslaved and colonised peoples, women and the working-class in the West. History has changed a lot, but there are still plenty of people who revel in the old sort of imperial history.

Just months before I started at UCRN Terrence Ranger was deported, not just for his activism but for teaching the wrong sort of history, he’s had lasting impact on the new History. Shortly after UDI historians and anthropologists were imprisoned and deported by the Smith regime in an academic purge – History as a discipline matters as much as the simple stuff in the past.

I guess we both lived through that shutdown of academic freedom that happened under UDI and Ian Smith and apartheid South Africa. You must know of the Principal Walter Adams of UCRN who was appointed as Director to LSE in London and sparked the sit-ins about academic freedom there in 1968 that led to the student revolution when I was there failing to study sociology!

Your book Remnants of Empire

https://remnantsofempire.com/

does something very important in recording the lives and opinions of the ordinary people who in the end, are those who make history. We do need more books like yours and Zambia needs them now more than ever.

This is a very belated reply – your comment is really interesting and in an age of fake news – its very important. Without history, we are living on quicksand and losing our feet and yet – thinking of history in places where there are no written records – is that where history is in constant recreation and what governs – if that’s the right word – its construction? In Zambia, I felt tradition was reinvented every day and was, therefore, alive and adaptable. In Britain, the idea of tradition as something past and fixed – and therefore ‘good’ seems to make us prisoners.