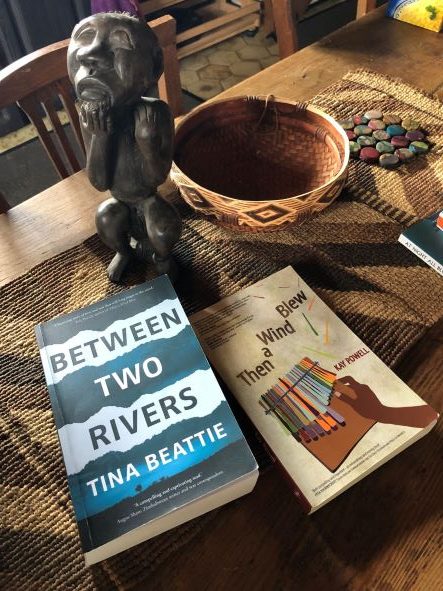

Last night I took part in the online book launch of Tina Beattie’s novel Between Two Rivers, a book I did enjoy reading. Among the panellists were Chiedza Musengezi, Kay Powell and Godess Bvukutwa. I knew some of the participants but I wish I had known everyone as the discussion was interesting and relevant not only to African women writers but to writers from every diaspora.

The discussion raised a conflict central to myself and my writing.

Who am I? What am I? Where do I belong? If I’m not African am I British? If I have a French passport but I’m not a native French speaker am I truly French? Will I always be a migrant and exile? Once I was a refugee and a criminal – am I still in what I write because of my heritage and my skin? My mother’s family went to South Africa 200 years ago as poor migrants. My father’s family planned a comfortable life as settlers and farmers in Rhodesia 100 years ago and failed because of the Great Depression. I was happy in the cosmopolitan metropole of London for 6 years. My heart will always belong to Zambia and my 22 years there during the liberation wars. I do, however, love my French rural life even while climate change and drought burn up my potager.

What can I do and what am I allowed to write?

Prisoners of the past?

What I do is write my African self and include bits of my English and French self. After all it’s the only thing I can do though I’m warned every day about the dangers of doing that. Britain is starting to acknowledge its colonial and slave-trading past and some of the discourse sees the divide between victimhood and guilt as a straightforward question of skin and colour. That is far too simplistic a concept for any thoughtful writer, particularly those who are diasporan. Few of us are just what we appear on the outside. Few of us are always sure what we feel on the inside.

What is a stereotype?

Last night a question was asked about whether we write stereotypes into our stories. Stereotypes are fixed ideas often expressed as jokes or threats that demand that people retreat into their nationalist identity. They are not easily changed. Most white Africans resorted to stereotyping black Africans and expected other whites to conform but not all people did and not all people ever do. People occupyinng positions of privilege who are therefore not challenged about their identity are at risk of living as a sterotype. People who are stereotyped by others resist their stereotypes just as women resist being stereotyped. Resistance means avoiding stereotyping other people. Perhaps that is why women writing Africa write as often as they do about difficult and contested events and change and changing ideas.

So many other questions

There are of course many other questions and issues – language, culture, experience, history as well as the translation and expression of ideas through nuance and idiom and faith.

Citizens of Nowhere

‘Citizens of the World are citizens of Nowhere!’ declared Prime Minister Theresa May in 2016. That was a call to nationalism in Britain. That call was followed up by the Home Secretary Priti Patel, a daughter of Indian refugees from Uganda decreeing that refugees are citizens of nowhere except a Rwandan hotel. I may be privileged enough to be considered a citizen of the world but does that make me and other diasporan novelists ‘writers of the world’ rather than writers with nowhere they are permitted to write about? Are we always to be like Camus, an ‘Outsider’ – the ‘Outwriters’ – those who are ex Patria? Outside the Motherland? Is that why it is so hard for women writing Africa to get published?

The power of marketing books

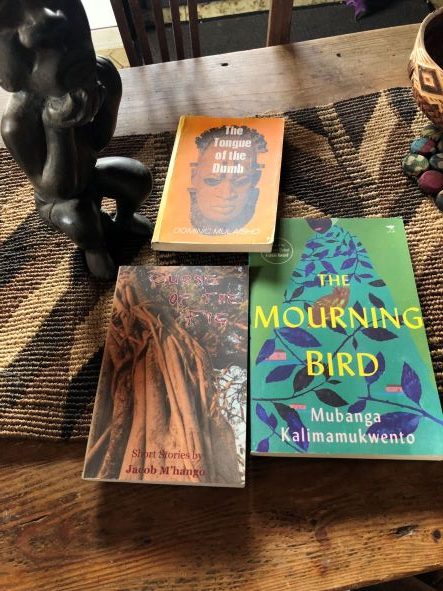

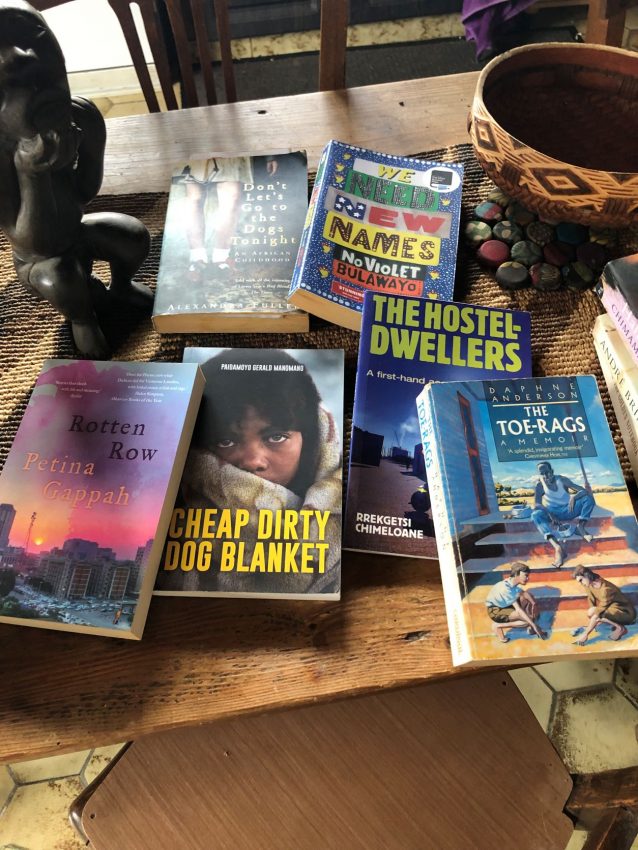

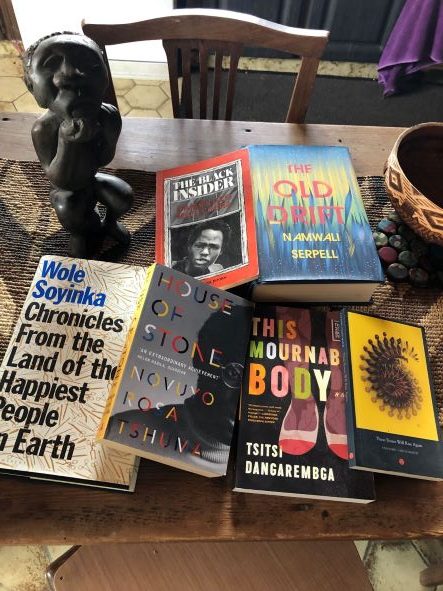

Women writing Africa are faced with huge problems. It is necessary to build up a readership in Africa and therefore a market for books that are affordable. The most successful African writers are published outside Africa, study and teach outside Africa and the most prestigious prizes are also awarded outside Africa. How do we change this in a digital world where mobile phones are what people read and the books we write are not considered easy to market outside Africa. Some of us have had to chose to self-publish but even this and the printing of our books is often done outside Africa

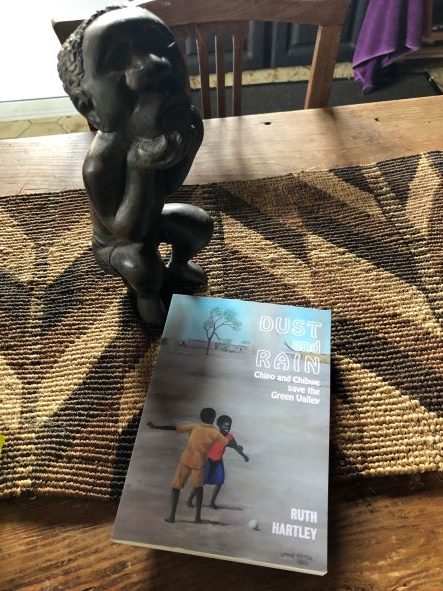

African writers have to be very grateful to publishers like Irene Staunton of Weaver Press, Fay Gadsden of Gadsden Publishers and Colleen Higgs of Modjaji Books. Three women dedicated to publishing books by Africans and by women. It is Gadsden Publishers who have given me my first real break by publishing Dust and Rain:Chipo and Chibwe save the Green Valley.

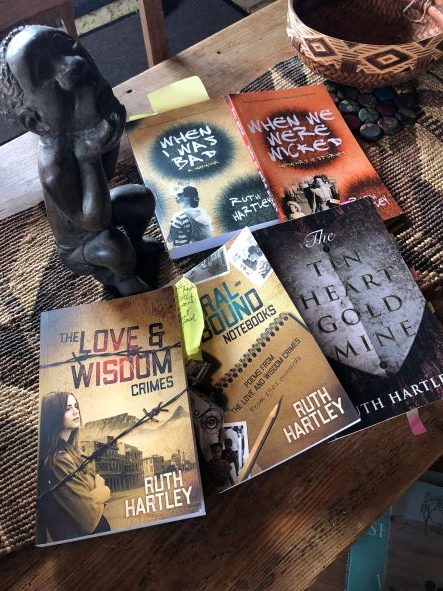

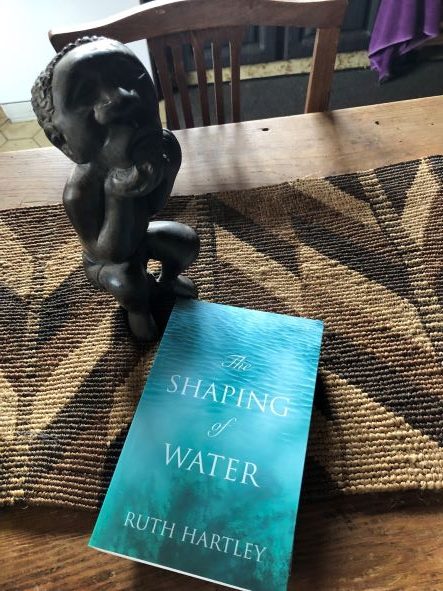

By the way the small ironwood sculpture of the thoughtful man is by a friend of mine, the artist Patrick Mweemba Siabokoma and the cover of my book by another friend and artist Style Kunda.

2 Comments on “Women writing Africa”

Keep asking the questions, Ruth, and stay brave! Even when we think we have enough life/world/political experience to know (some of) the answers, we can always go deeper. In any case, each of us seeking the answers is a slightly different person at the time of each asking … especially if we’ve been informed by reading any women writing Africa! 😉

Thank you Tia! I ask more questions the older I get but it is good to be encouraged to keep on doing this! It is also hearteninng to meet and to talk to other writers and artists who are engaged with similar questions. Better to meet people in person but very grateful for Zoom debates and online conversations.