Wicked women

Bridget and I are the same age and we were both ‘unmarried mothers’ a long time ago.

Bridget became pregnant in Ireland at 17 years. She escaped to London but was sent home by a priest to the torture of the brutal Bessborough home, a Catholic institution for unmarried mothers. Her tragic story and the death of her baby is recounted here. I became pregnant at 22 years in Cape Town, South Africa. From a very different background, with strong political convictions and different intentions, I too escaped to London. I was more fortunate. There I was helped by progressive and proactive women first in the Defence and Aid organisation and then in the National Council for the Unmarried Mother and her Child run by the wonderful Pauline Crabbe.

Sinful sex

Bridget and I were both ignorant about contraception and sexual intercourse. Bridget, a Catholic, was deeply ashamed. I, a Marxist then, was terrified that I might go to prison under the South African miscegenation laws. I also knew that my pregnancy would shame my family and I wanted to spare them that.

Pregnancy protection

I was once asked why I hadn’t used contraception then. I laughed. What was life like then? Well – kissing a boy was very naughty and led to worse behaviour! Women and girls were not in charge of their bodies or their bank accounts or contraception. Contraception was only for married women. Sex was sinful outside marriage. The subject was scandalous and never mentioned. Even in London condoms were not displayed at the drugstore. The chemist kept a few wrapped in plain paper in the top pocket of his coat so that a married man could sneak up at a quiet moment to ask for them. Married women secreted a douche – a large red rubber balloon with a long black snout – in the bathroom to wash out and disinfect their vaginas after sex. Occasionally that also prevented a pregnancy.

Unmarried mothers

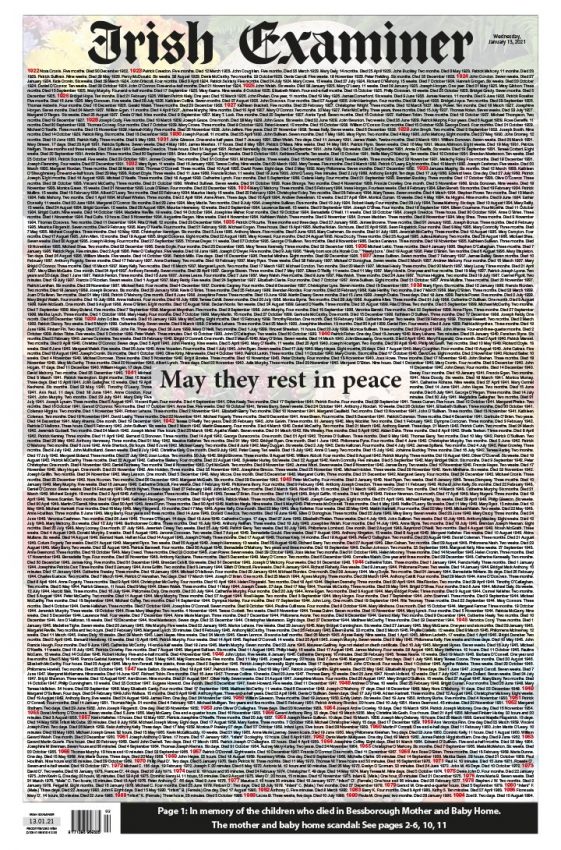

Pauline Crabbe found me work as an au pair with a London family. I’ve written about that experience in my memoir When I Was Bad. I was to take over the au pair job from a young Irish woman who was due to go into a mother and baby home and give up her child for adoption. She would have to nurse her child for 6 months first. I cannot imagine how painful that separation would be for her but her experience in London would not have been as cruel and damaging as if she had been in an unmarried mother and baby home in Ireland. By comparison, I was lucky. I was going to keep my child at all costs and I refused to feel ashamed. I had, of course, no idea about how hard life would be, though never as dreadful as Bridget’s experience. Reading the story of Bridget written by Deidre Finnerty on the BBC reminded me of that young girl I called Colleen in my memoir. I found out little about her in the 2 weeks I was with her. Probably she was a girl like Bridget whose choices were also limited and painful? At least she escaped from the horror of a place like Bessborough. I remember her as bright-faced, smiling and pleasant. I hope that she went on to be happy – I’d love to know what happened to her.

Survival means changing.

I, on the other hand, didn’t know anyone or anything. I had been in London about a fortnight and I had nothing but the desire to keep my baby safe. I was one of many young women in London who were making that choice. We had the welfare state and National Assistance and eventually we got nurseries and contraception, new lovers and joined the Women’s Movement and tried to change the law on abortion and women’s rights. Unmarried mothers in those days found that their children were literally outside the law – illegitimate – legally classified as bastards.

The deaths of souls

The dreadful abuse, the stigma and the shame that Irish girls and women were subjected to would go on until the 1980s. The Magdalen Laundry sung about by Mary Coughlan, the forced adoptions made into the film Philomena starring Judy Dench tell a few of the many tales about it. It’s a perversion that a religion that teaches repentance and forgiveness has been responsible for the suffering of living souls who still drown in despair and grief and the deaths of newborn souls whose stories will never be told. I find myself thinking that the souls of the nuns and sisters who treated women and girls this way – girls and women probably from similar backgrounds to theirs – may also have died or shrivelled – but then as the story of Philomena makes clear – life is complicated. Beware of judging!

Digging up the dead to give them dignity

Last week I wrote about digging up bones. I’ve been often told to let the past go but it’s the other way round. It’s the past that won’t give up on the present and keeps distorting our future. It’s the secrets from the past that I’ve kept hidden that have stirred themselves and returned to haunt me and my children. Perhaps George Santayana’s aphorism that ‘those who do not learn from the past are doomed to repeat it’ isn’t helpful because we seem doomed to repeat history even after we learn it. Perhaps the purpose of understanding the past is only to make us humble, compassionate and help us be forgiving?