We all own the River.

That’s what we believe. The world of nature is ours and we can do what we like with it. The River belongs to us. We can use it – we can waste it – we can worship it. Not one of these ways of looking at the River tells us what it means to be the River itself. We think we know of and all about the River. But not one of these methods of evaluation and study tells us the story that is the River’s own story.

Telling our stories of the River

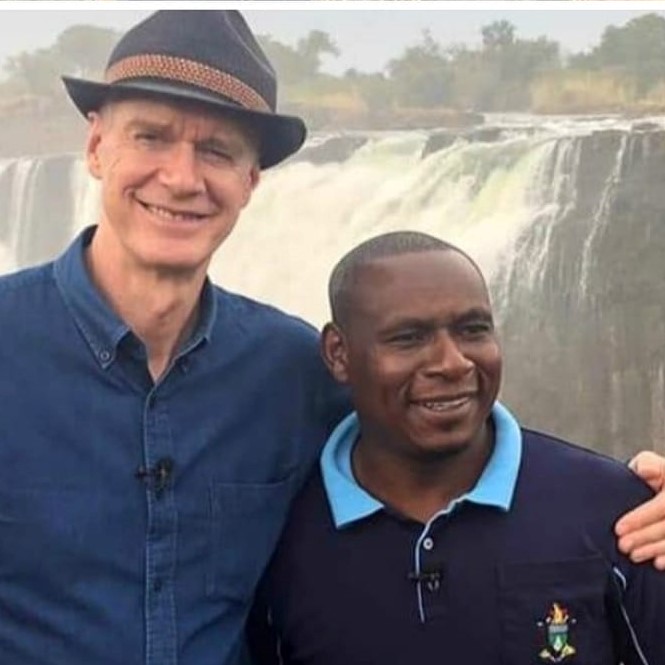

The Great River Zambezi became the focus for a million different stories in a social media post about the Victoria Falls this month. Known by the African peoples as the Mosi-O-Tunya – the Smoke that Thunders – it was renamed by Dr David Livingstone in honour of Queen Victoria. That was Livingstone’s way of giving the River to the British Empress of India. By saying that angels in their flight must have stopped to marvel at the magnificence of the Falls, he gave the River to Christianity and missionaries. Colonial governments ignored what the River meant to Africans who thought of the River as the great Snake God – the powerful Nyami-Nyami who brought life to the people who lived by the River. Livingstone hoped, however, that his story of the River would help bring about the end of the Slave Trade even if it brought colonialism to that part of Africa.

Different stories of the River. Different visions of the River

Did Livingstone only see the material fact of water plunging into a vast rocky chasm? Did he see angels above it? How does the transformation of the River into spray and mist and sound, make us understand the power and the spirit of the River? What stories are science? Which stories are fantastic? What stories are spiritual?

Climate change, drought, tourism, science, scientists, reporters, the local people, lovers of the River, fish, flora, and fauna.

Stephen Sackur was reporting on climate change, drought, and famine in the region for the BBC. These are all important and real problems. He chose to illustrate his piece with a photo of the Mosi-O-Tunya at its lowest season and at its driest point. In fact, the levels of water in the river are not about local droughts as the Zambezi is fed by rainfall in the Congo region. People in the tourist industry were furious, fearing damage to their businesses – they also want people to enjoy the exotic and unique beauty of the Falls. Scientists were outraged because the story wasn’t factually accurate – they think truth and provability matter – which they do. A few people protested that there is a drought and there is hunger. – they’ve seen people suffer from both. Some of us know that climate change is happening – we’ve observed it. A few think it isn’t – they prefer to hope. Everybody thinks their stories are huge and important but the really significant story is the one told by the River about all of these things. Are we listening to the River? What is it saying about itself? Are we able to hear its story?

My stories about rivers and the River

In my novel The Love and Wisdom Crimes – Jane goes to the Msimduzi River at a time of sadness and change in her life – “Further away the river would go past African townships, then by rural Zulu villages, passing through the Valley of a Thousand Hills, until it ended up among the suburbs and industries of Durban. By then it would have tasted, touched, carried, and deposited almost every conceivable human, animal, mineral, and chemical detritus possible, as well as fed, watered and sheltered all kinds of life including crocodiles, mosquitoes and children. Jane thought of the tears she could not cry. Even if she had wept for weeks right where she was squatting, her tears would not reach the river; they would not even splash down with the force of a single raindrop. How many people would be needed to cry a river?”

More stories about the Great River

In The Shaping of Water – Father Patrick Brogan has to persuade the Basilwezi to leave their homes on the banks of the Zambezi to escape the rising waters of the new Kariba Dam and years later Manda is reassured to learn that the River is not lost and gone but continues to flow as an identifiable current right through the enormous Kariba Dam.

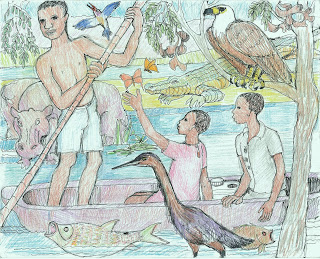

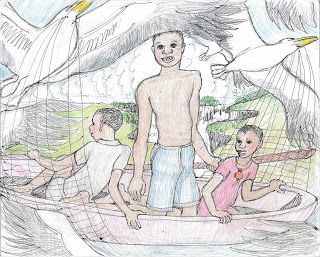

In my children’s story, The Drought Witch, Chipo and Chibwe search for Makemba, the Wise Woman, at the Source of the Great River. Near the end of their quest, Chipo feels despair and is comforted by the River. “When I travelled with the Rain Spirits, they took me all over the world, so I’ve seen the sea. I’ve seen that Water is Life. I’ve seen that the River is always the same and always changing. The River that Chibwe, Mokoro and I travelled on has left us and gone on ahead of us to the sea. The River that runs past me now is a different river that knows different people. I’m only one tiny part of the River that is Life. All I can do is be that tiny living part of the River of Life. No matter how much I cry, that is all that I am. The Great River has spoken to me. I know what I must do.”

Zambia and the Zambezi River

It’s Christmas and holiday time and I will be returning to Zambia and the Zambezi River in search of new stories. It may be a while until I post again so greetings to you all and best wishes for 2020

4 Comments on “The River’s Story”

Safe travel, Ruth – and a blessed Christmas…..

Jon

Your artwork in this post really moves me, Ruth.

I love the painting of the river, and also the river drawings from The Drought Witch.

May you find even more inspiration in Zambia this Christmas season.

Hope you have a wonderful time and find many new African story plots for your readers! Merry X-mas too!!

I love the artwork in this post too, safe and enriching and enlivening journeys and season’s joy for you all