Returning to the past to build the future

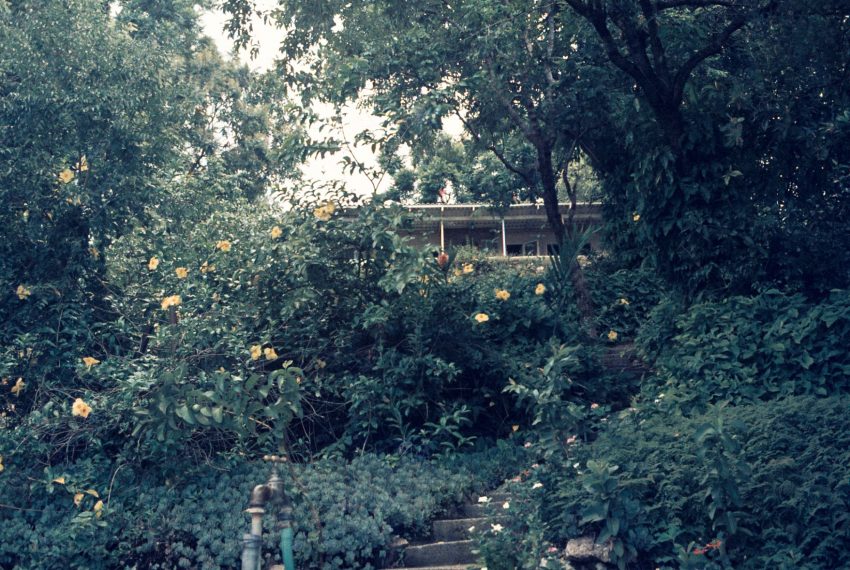

This year I time-travelled back more than 30 years. I returned to the Ridgeway Hotel in Lusaka to the place where golden weaver birds build their nests above small sun-worshipping crocodiles. Here, there once was the excellent Zintu craft shop, a regular Zambian ladies lunch, an Independence Day National Art Exhibition and gin and tonics on the verandah under the management of Richard Chanter.

On this occasion, I was meeting Daniel Sikazwe, journalist, broadcaster and PEN member who was interviewing me about my novel The Shaping of Water. The Ridgeway was as pleasant as ever! As with the Alliance Francaise event compered for me by Daniel, it was a very enjoyable interview. Daniel asked me penetrating questions about the reasons I wrote The Shaping of Water, and the truth of the facts in it. “It’s a book that should be standard reading for Zambians,” Daniel said. “It tells of a part of our history that is not known about.” And so we talked about how I came to write this book and the problems of writing cross-cultural history as a novel.

A Scottish village in Africa

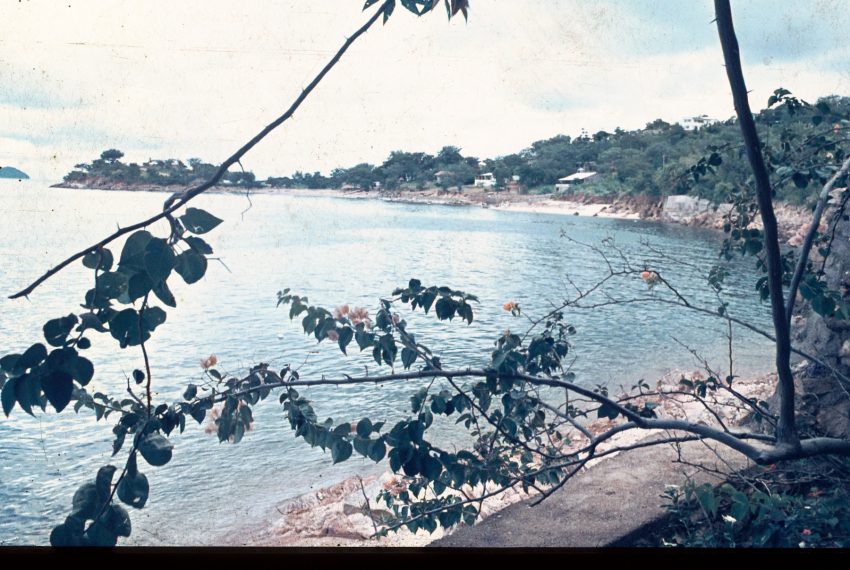

In 1972 I found myself living in Siavonga, the new township on the Zambian shores of Lake Kariba built to house the British companies constructing the North Bank Power Station. There were three classes of housing for white people. Executive housing for the consultants, middle-grade housing for the engineers and their families and terraces of single rooms for the Scottish workers from the slums of Glasgow.

The new housing was perched high above the lake on the steep rocky escarpment that once plunged vertically into the Zambezi Gorge. Reaching the lakeshore demanded a marathon physical effort in the tremendous heat of the Lowveld. The Zambian community lived in traditional villages around Siavonga.

The bigotry and racism of this tiny imported Scottish community surpassed even that of the white Rhodesia I had grown up in. Mitchell Construction despised Zambia and was busy embezzling funds provided by development agencies for their Jubilee Tube project in London. They went bankrupt inside a year and abandoned the power station.

The Queen Mother and the Colonies

13 or so years previously my first visit to Kariba had been an ordeal. My father, still deranged from his divorce, took me to see the dam wall in his Austin van. “I only buy British cars,” Dad stated. The van was burning-hot. The dirt road was crowded with construction lorries. The dust choking. Kariba North was home to Italian workers who leered at me.

The dam wall was a broken curving rampart holding back a gleaming river in dry bush. For white Rhodesians, it was triumphal proof of their power and control in Africa. The Queen Mother was to open the Dam in 1960. It was planned to cement the Federation of the Rhodesias and Nyasaland together but that political bodge was already coming apart. Freedom fighters would soon be crossing the Zambezi valley to the sanctuary of a newly independent Zambia which supported them and the wars of liberation would soon begin.

The lakeside cottage of my dreams and my story

In spite of my previous experiences at Lake Kariba, I was to spend some of the happiest times of my life there in a small, primitive cottage without electricity. This cottage became the setting for my novel and there were many reasons for that choice. The lake is beautiful in itself. It is, however, a giant unpredictable experiment that is changing the natural environment of the region. Every time I went there I learned something new about it and became more engaged with it.

For a time the liberation wars made it impossible to go there safely. On one occasion, the Rhodesian Air Force machine-gunned Siavonga, the hotel and bar, and the nearby village killing women and children. These were hard times for Zambia, a Frontline State, which hosted the ANC and ZAPU armies.

My early life, my education, and my experiences in South Africa made me a supporter of African freedom but I had yet to learn of the displacement of the Tonga people of the Zambezi Valley. That story about the Tonga people, researched by Professor Elizabeth Colson, would become an essential part of my novel about Lake Kariba.

A novel about displacement and war and ordinary people

My novel has neither heroes or villains. It’s about ordinary people caught in extraordinary times who mostly try to do the right thing as they see it. It’s not about the famous people who, we are told, shape history. It’s about how history shapes us, maybe deforms us, maybe makes us, but also about how even if we are displaced we cannot escape our shaping. It is about how the great Zambezi river was trapped and reshaped into a huge dam and how that immense volume of water continues to shape the land and to shape the people who live around it and who depend on what it provides.

2 Comments on “The Shaping of Water”

Evoked wonderful memories of our time in Zambia from many fun times at the Ridgeway to the glorious weekends at Siavonga

Hi Chrissie – I’m so glad that my post reminded you of some of those wonderful times down at the lake. It was so beautiful! – and so hot! I’ll go back again someday!