An interesting paper

Gijsbert Witkamp has written an interesting paper on his blog Art in Zambia about Henry Tayali, and Fackson Kulya, two artists I knew through my work at Mpapa Gallery when Bert was away in Europe between 1979 and 1988. Bert describes Henry as an ‘academic’ artist and Fackson as a ‘folk artist’. This might describe the difference between a ‘westernised’ artist and an ‘authentically African’ one and relate to recent and important discussions about neo-colonialism and its effect on culture. As Zambia has very little recorded art history of the first 30 years after Independence, perhaps my post will be of interest in this connection.

What brings about change in a society?

On October 24th 1964 at midnight Northern Rhodesia became Zambia. What changed in those few important and significant moments? The answer is very little changed right then in Zambia’s infrastructure. There was the same number of schools, of colleges, hospitals, teachers and graduates before midnight and after midnight. The same number of people believed in Zambia and freedom from colonialism and the same number of people were afraid of it. Zambia’s mines were still owned by South African companies. The work of developing Zambia was still to be done in a region that was to become involved in the Cold War for another 30 years. Nothing would be simple or quick. The people and the events that cause change can begin long before the change takes place. Change and the things that put brakes on it are woven into history over time and those motors of change are themselves a weave of the progressive and anti-progressive. This makes it impossible to tidy history into separate periods marked by abrupt breaks or to sort people into those categories as well. We are all constructed from complex interlinked personal histories. What makes changes is the commitment of individuals to work for a better future. In Zambia, one of those people was Henry Tayali.

Henry Tayali

Henry and I were the same age, but before Zambian Independence our lives were quite different. I was born and grew up in the colony of Southern Rhodesia while Henry was born in the Protectorate of Northern Rhodesia. We both wanted political change and equality. We didn’t know each other when we were teenagers, but a painting Henry made at the Mizilikazi Centre in Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia, where his parents lived, was shown at the National Gallery in Harare (then Salisbury) and I was very impressed by it. Henry said later he was furious that his work was curated into a segregated African art section with the self-taught intuitive (naïve) artists. He thought all artists should be equal and in Southern Rhodesia they were not. When I finally met Henry many years later at Mpapa Gallery, he was a better qualified and much more successful artist than I could ever hope to be. He was also an excellent mentor and a political and art activist who set very high standards and was dedicated to helping Zambian artists.

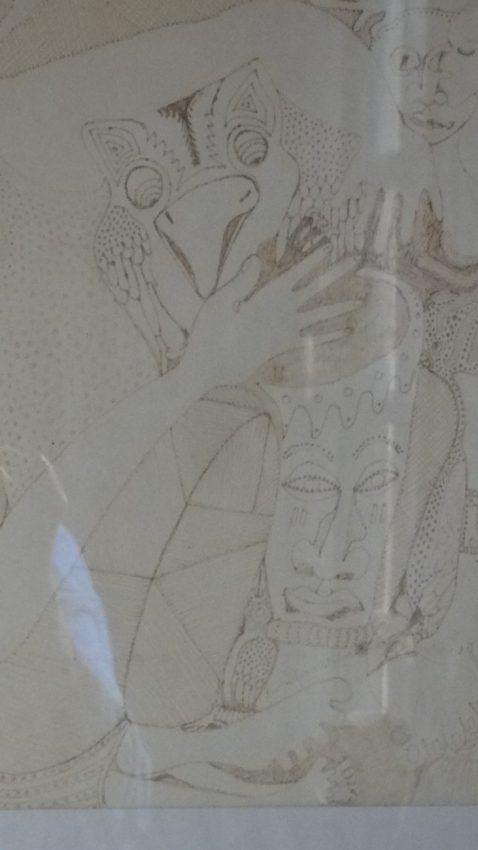

Fackson Kulya

Fackson was a delightful person but absolutely infuriating to work with at Mpapa Gallery. He was immensely talented but his work could be very uneven because he cared little for its durability and sometimes used inferior materials. He would promise to bring work to the gallery and then either not complete his work or sell, or even give, it to someone else. For those reasons it was hard to build up a reputation for him outside Zambia and while we loved Fackson for his creativity and huge talent we were sad to think that his work might not be saved or valued even there. I have a pen drawing by Fackson that has tragically faded away over time. For Fackson, his tribal culture was of immense importance. He told me once that he was far too busy becoming a traditional healer to make art – that was an important and significant role – but I did hope that he would continue to make art as well.

Different ways of making art

Mpapa Gallery worked with many artists who had very different ways of making art. We supported non-academic and self-taught artists, artists whose art questioned colonisation as well as academically-trained artists who worked in western traditions. Henry and Fackson are excellent examples of the broad range and diversity of Mpapa Gallery’s artists. Artists aren’t obliged to make politically correct art or conform to current trends and fashions. Art and artists will continue to explore ideas and challenge preconceptions as well as make objects of beauty. Mpapa Gallery existed to support all Zambian artists at that time and saw itself as an agent for positive and political change.

One Comment on “Mpapa Gallery, westernised art and tribal heritage.”

Hello.

I have a beautiful Fackson Kulya statue ‘Woman with a water pot’. Would you like photos of this? It’s an exquisite piece. I’m giving it to my daughter as a wedding present so won’t have it for much longer.

I worked with Mick Pilcher & Cyntia Makromallis as a graphic designer from 1977-1980.

I liked Henry immensely & was saddened by his failing health. Fackson was so likeable-a cheerful soul whose work reflected his spirit.

Thank you for a good article.

Best regards

Maryanne Heyman