A time of discovery and learning

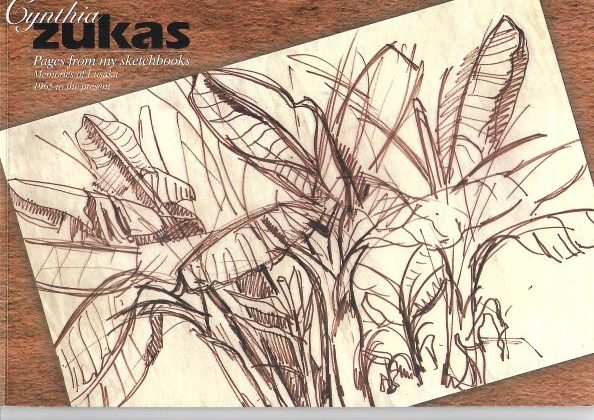

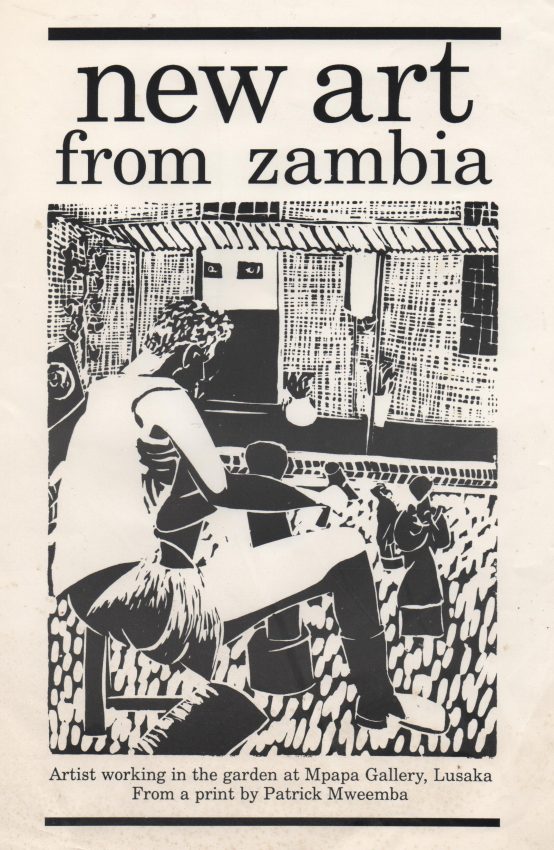

Looking back at Mpapa Gallery we faced several important challenges which will interest Zambian artists today. The fact that the gallery was run by three practising African artists – me, Ruth Hartley, Cynthia Zukas, Patrick Mweemba, and started by Joan Pilcher, who had studied art at the Evelyn Hone College meant that we were all engaged with the hands-on process of making art and not just in selling it. We were also each different as people and artists as you can see from the work we made above.

Working with Zambian artists at Mpapa Gallery was a time of intense learning for me. I had to rethink perceptions I’d acquired without realising I’d absorbed them. A friend and political activist in South Africa had advised me to learn from other people by understanding what they thought and felt. All the same when I started work at the gallery I didn’t have any idea what to expect. I’d long ago rejected the racism and inequality I’d seen around me as a child and though disappointed by my art school I’d had a good tutor on my teaching course who made me realise that creativity is innate and should be nourished not controlled. So, what could Mpapa offer that Zambian artists needed? As I worked to fulfil those needs I also learned much that would help my own art. That, however, is another story.

The artists and the gallery

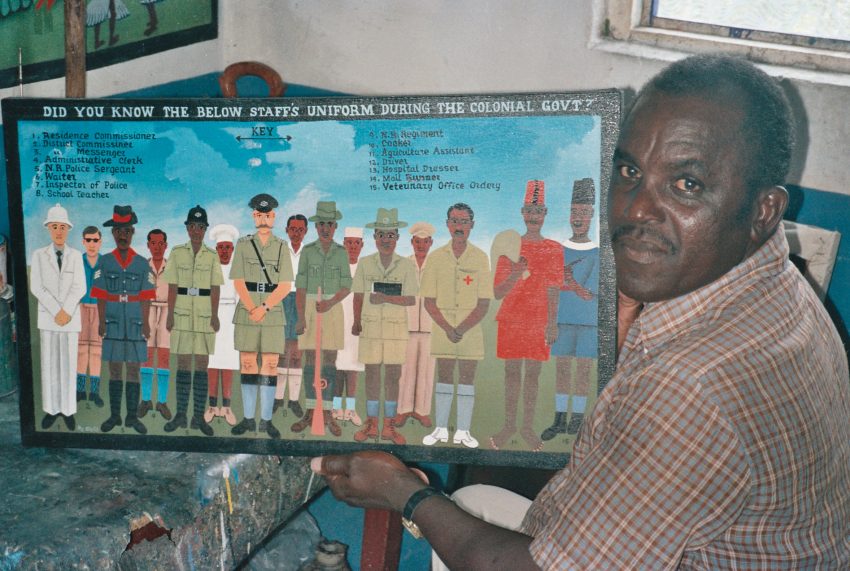

The artists I met at the gallery were different from each other in every way. From Henry Tayali, a contemporary abstract expressionist with an MA, to printmakers like Patrick Mweemba, David Chirwa and Fackson Kulya, Stephen Kappata and sculptors like Tubayi Dube and Eddie Mumba, the range was very wide as is clear from the images above. In Britain a gallery usually concentrated on one style of art – abstract, landscape, prints, intuitive, expressionist, avant-garde and so on. Their artists would be art school trained and need no education from the gallery. A British gallery would also focus on a specific market – collectors, tourists, art museums, or homemakers. Mpapa Gallery, on the other hand, had to be eclectic and inclusive because there were so many different artists working in different ways with different materials and techniques, and with different education, experience, ambitions and ideas. We also had to create new markets and expand the limited one that existed. It’s a laughable idea that the gallery could dictate one particular style or art genre even if we’d wanted to. Our aim, however, was to provide the support that Zambian artists needed to achieve the best they possibly could and we had to do that without funding or financial support or even approval from the government.

Colonial culture, education and critical discrimination

At that time Zambia still had an education curriculum designed for British standards which meant that Zambian art teachers studied nineteenth-century European artists – and Picasso. The lack of access to museums and art galleries meant that Zambians had no exposure to world cultures or even their own African history. Apart from a small number of people like Tayali, Lorenz, Kapwepwe, Musakanya, Zukas, Pilcher and the teachers at the Evelyn Hone, there was ignorance about art, culture and even domestic style throughout all social groupings in Zambia.

Mpapa Gallery and art and culture

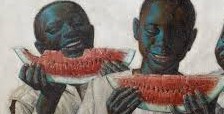

Early on an artist brought his work into the gallery and asked me for an exhibition. He had copied a Vladimir Tretchikoff painting of an African child eating a watermelon. He believed that this was the kind of work Mpapa would want to sell but even then Tretchikoff was considered both racist and kitsch. I had to think quickly. What was best for this artist? What was best for the gallery? My task was important and required diplomacy.

- I had to bolster the artist’s confidence in his innate ability,

- praise the good qualities in his work,

- explain that copying art was plagiarism and unacceptable,

- explain what professional behaviour was expected from an artist

- encourage him to be more discriminating in his aesthetic choices

- encourage him to find more authentic and original subject matter

- never at any moment tell him what to paint.

- make it clear that the gallery wanted the best for him

I wanted him to return to Mpapa with a better painting and I was very happy when he did. He would go on to study at an art school in Britain and to become one of Zambia’s best-known artists.

Kitsch, good taste and aesthetics

It was clear that the gallery’s task was extremely complex. Everything I’ve mentioned so far can spark hours of debate and provide enough material for 100s of university theses. Then we had no guidelines and there was no internet for research. We had to find our way using first principles – freedom of expression, no racism, no sexism, professional standards and authenticity while providing support for Zambian art and artists. In my next post I’ll try to unpack some of the issues raised here – for example what is aesthetics – what’s considered good taste – why some art is labelled kitsch. – what is beauty? I do hope that this discussion will continue in the comments that you – my readers – will make – please!