This is a story about doors and wages and a migrant. It ends with a death. A migrant is a person who moves from one place to another in order to find work or better living conditions. Who has never or not done that?

Long ago at the start of things

It was 1973. Mike and I had been one year in Siavonga, Zambia, and a bit of a year in Lusaka. Zambia was just entering its 9th. year as a new Republic. We went there to improve our financial situation. Everything was changing – everything was going to be different, but we had no idea how that would manifest itself. I had been 6 years in London ,but had grown up in apartheid South Africa and rural Rhodesia. I knew very little about Zambia and my radical political idealism was only theory– not yet put it into practice. I had much to discover and learn and what would Zambia teach me?

An ex-pat life

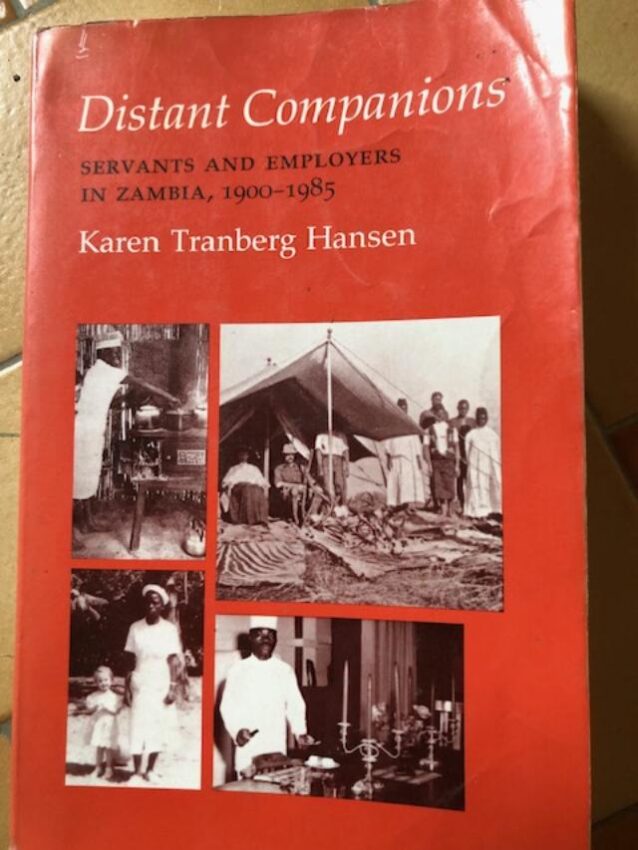

Mitchell, the first ‘migrant?’ company (British) to employ Mike and me in Siavonga, ripped off Zambia and then went bankrupt, so next Mike got a job with mines and banks running a clinic in Lusaka. We had become expatriates with a protected and privileged life that included a rent-free house, and salaries for a gardener and house staff. Unemployment was high and long queues for housework jobs formed at every ex-pat gate. You either employed someone or spent the day sending people away.

Zambia was changing

We wanted to see Zambia succeed and prove itself as a progressive African nation, but how could we contribute to that dream? I didn’t want to be ‘just a housewife’ and so I applied for a work permit and that meant I would need domestic help with the house and my children.

What did I do differently?

Well – I planned that any person who worked for me would work ‘union’ hours, or 8 hours a day. Nobody would ‘wait’ on me or anyone in my family and I would continue to cook our meals. After all, I’d been in the Women’s Movement and had approved of a minimum wage for babysitters that, ironically, we couldn’t afford on Mike’s junior doctor’s salary. After Zambian Independence, there had been an attempt to legislate for fair wages for house staff, but that concept disappeared rapidly with inflation and traditional practice. Diplomats paid high wages and the rest of us either what we could afford or what was included in our work contract.

Front doors, back doors and trade entrances

Does anyone know what the difference is nowadays? Do you have a street entrance and an alley exit or a garden door? Do you live in a flat with one entrance? Nowadays I go in by my front door and keep my back door as an escape route, but back then door use was loaded with symbolic class and status. Back then as a ‘modern ‘ (read fair) employer, I interviewed Joseph and Betty, my new house staff on the front veranda, though their living quarters were in the back garden.

Mr Brown Zulu

Mr Brown Zulu called on us. (His first name really was Brown.) He was well-spoken and looked like a modest and tidy schoolteacher with a tweed jacket, white shirt and tie. He was a poor man, he said, who needed help with after his brother’s death. I made him tea, and he broke down and cried quietly into his handkerchief. Of course, we found some money to help with the funeral service. He was very grateful, and we felt good. I was both mortified and impressed to discover a few days later that he was a confidence trickster of remarkable talent who had taken money from all the local expatriates in two days. We were well-played. Sadly, that meant I was less trusting when our next visitor arrived.

The old man

Mr Simon Phiri, the old man might have been Brown Zulu’s father. His suit was older and shabbier and his manner was respectful and quiet. He was slight and shrunken and he needed money he said because he was hungry and hadn’t eaten for a while. My 5-year-old daughter took his hand and the three of us walked round to the back of the house and we all went in by the kitchen door.

‘Joseph,’ I asked, ‘Please can you make some tea and cook some nshima for Mr Simon Phiri – perhaps he can tell you what he needs.’

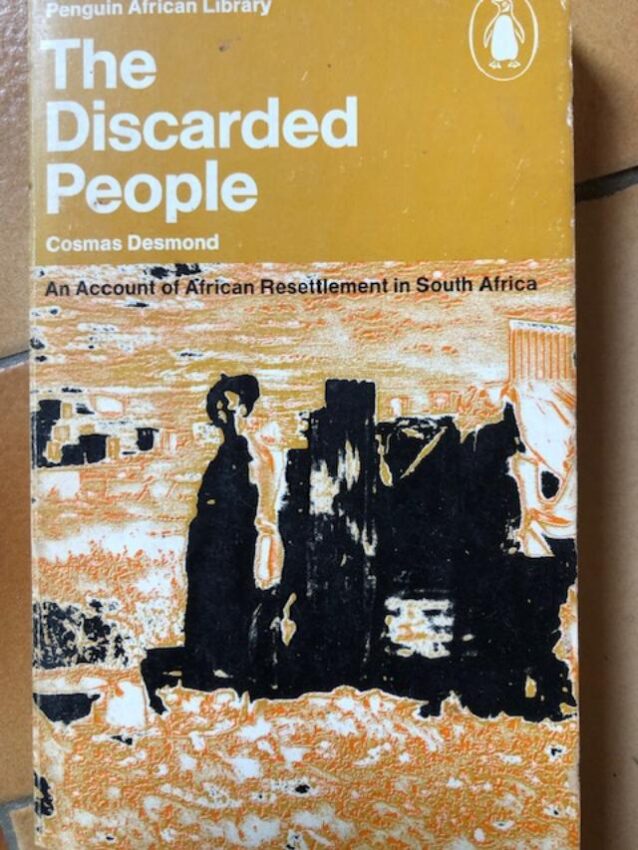

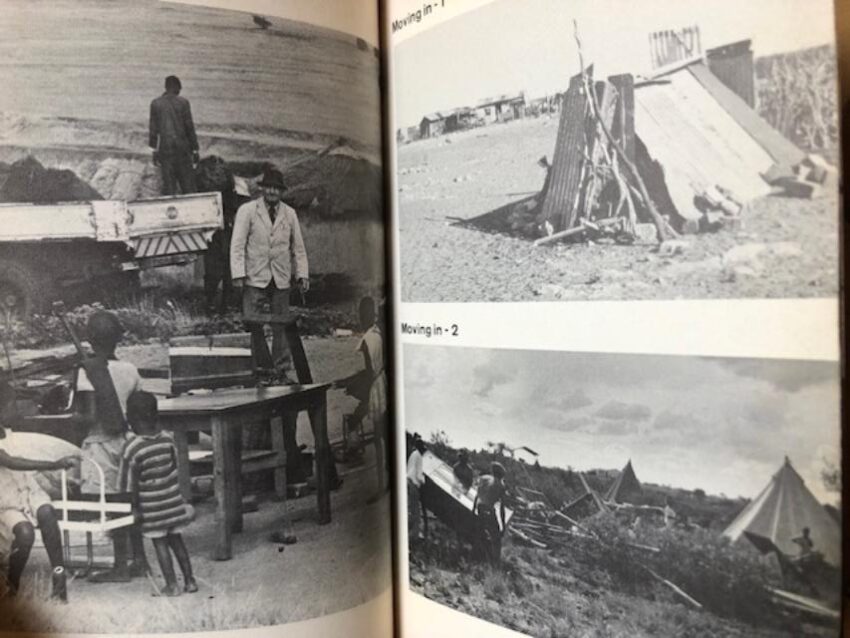

I left them to talk in their shared language, and later Joseph recounted the old man’s tragic tale. Mr Phiri was Zambian-born and had gone to South Africa as a migrant worker when he was young. He had spent all his life there, married, and had children and grandchildren. Then apartheid caught up with him as it did with all non-white Africans. Under the Group Areas Act he was deported to his ‘homeland’ back in Zambia. Mr Phiri returned to his original village in the bush looking for relatives, but it had vanished, and no inhabitants could be found. He then walked back to Lusaka, but had no money left and was starving. Mike took Mr Phiri to the clinic for a check-up and to see if he could access some help for him. An institution was found to care for him but Mike diagnosed lung cancer and Mr Phiri died a few months later. I grieved for him and was furious with the cruel apartheid government. I had seen people starving in South Africa in 1965 because of the Group Areas Act.

We are all migrants

I am tired and dispirited by the current media portrayal of migrants. After the British Empire ended slavery, it built its economy on migrant labour that it moved around the world. It was the same for the South African and Rhodesian economies. Colonists and settlers were also migrants but the railways, rubber and sugar and gold mines and farms they controlled and benefited from all depended on migrant and indentured labour imported from other parts of Africa, or from India. Mike’s family were Jewish migrants from Russia and Poland. My family were migrants from England and Germany to Africa and Argentina. I am now a migrant from England to France. Many of my friends and colleagues worked as ex-pats all around the world and were, after all, only high-paid and privileged ‘migrants’ too. I would like to recommend a memoir by Katie Hendricks called A Bend in the Road. Katie’s father came from Zimbabwe, not Zambia but he too was a migrant worker like Mr Phiri at around the same time. It’s out of print sadly.

Back door, front door, locked and barred gate

So readers, is the difference between you and me and a ‘migrant’ only a question of which door gives us access to work, hope and safety. Okay, perhaps your house is too small to welcome and feed the stranger – perhaps the answer for you then is to prevent wars, stop climate change and make people able to stay safely and happily where they really want to be – in their homes.